2018’s Top Films

There are two kinds of people in the world.

There are some people who, rather than merely “entertaining” themselves, watch the most important, the most beautiful, the most challenging, and the most thought-provoking films released each year; and there are some people who don’t.

The list below was created to assist the former.

_____________________________________________________________________

January 12th – Paddington 2 (2017), directed by Paul King

From Katie Walsh at the Tribune News Service:

“It seems miraculous when a film adaptation gets a much beloved character just right, but when the sequel is even better? That’s nearly impossible. That’s a unicorn. Director Paul King (with writer Hamish McColl) managed to set the bar high with 2015’s Paddington, and now, incredibly, King and co-writer Simon Farnaby raise it with Paddington 2, bringing the warmth and gentle humor of the late Michael Bond’s indelible children’s books to the screen, along with Britain’s finest actors …

Paddington’s tale is buoyed by the tremendous cast of performers around the animated bear. Gleeson and Grant might steal the show, but Sally Hawkins, Hugh Bonneville, Jim Broadbent and a wonderfully diverse array of actors populate Paddington’s London, a place that’s cozy and cheery largely because he is. Whishaw’s smart, wry and sweet voice performance as Paddington embodies the good-natured and gentle ethos of the character, and ultimately, the film itself.

King’s cinematic style, aided by Erik Wilson’s soaring, swooping cinematography and Dario Marianelli’s score, is a dash of Wes Anderson and a sprinkle of Jean-Pierre Jeunet, swirled around with a wonderfully fluid sense of airiness and light. It’s mannered, yet carefree, colorful, and evocative.

What these Paddington films express so beautifully is simply an overwhelming sense of goodness — a rare commodity in the world today. Paddington insists if you’re nice and polite, the world will be right. That notion has been so battered and bruised lately, you’d be forgiven for cynically thinking the little bear might have to learn that’s not always true. He does endure his trials, but, miraculously, the world bends to his will, not the other way around. Isn’t it wonderful — a miracle even — to see nice and polite prevail for once?”

__________________________________________________

January 26th – Hostiles (2017), directed by Scott Cooper

From Allan Hunter at Screen International:

“Hostiles acknowledges that American history is steeped in blood and hatred but still searches for signs of hope arising from the ashes of countless atrocities. Scott Cooper’s brooding western invests the genre with the psychological insights and guilty conscience of the 21st century. It may pay a commercial price for such noble intentions but it will attract audiences drawn to solemn, slow-burning dramas that give pause for thought …

Hostiles unfolds as a long journey from Fort Berringer in New Mexico to the Valley Of The Bears in Montana. Cinematographer Masanobu Takayanagi ensures that it is filled with sparkling images capturing the grandeur and changing landscapes of the American heartland. There are eye-catching images of fertile green plains, dusty desert mountains and riders captured against the dimming dusk light. There is no doubting the beauty of a country in which so many ugly things happen.

The widowed Rosalie becomes part of the company as they travel onwards. The journey is fraught with danger but filled with chances for sworn enemies to see the humanity in each other.

Christian Bale’s Blocker is a gruff, taciturn figure more likely to grunt or nod his head than utter a sentence. Hardened by all the killing and hatred, he is similar to John Wayne’s brutal racist Ethan Edwards in The Searchers (1956). Over the course of the film, Blocker becomes a changed man and it is a transformation marked by pensive moments, dawning realisation, lost friendships and anguish that all too rarely finds a expression. A fastidiously understated Bale is highly effective at conveying the deep waters running beneath his stern features.”

__________________________________________________

February 16th – Black Panther (2018), directed by Ryan Coogler

From Olive Pometsey at GQ Magazine:

“Black Panther is the superhero film we need to remind ourselves that all races are capable of greatness and that there’s room for everyone’s stories to be told … As I’ve grown older, options have still remained limited. Want to watch a film with a mostly black cast? Well, I hope you have a box of tissues at the ready, because it’s either going to be about slavery or the crippling effects of poverty and gang crime in the ‘ghetto’. This is why Black Panther is such a game-changer. It’s one thing to see a film where Hollywood’s black talent get a chance to shine, but it’s quite another to watch them create a world where their race isn’t weighed down by the oppression and prejudice that they face in real life.

Set in the Kingdom Of Wakanda, Black Panther presents us with a version of Africa like we’ve never seen before. A far cry from the distressing clips of poverty and disease that interrupt your soap operas and convince you to donate to charity, Wakanda is imagined as the most technologically advanced nation on the planet, a vision of an Africa that resisted the trauma of colonialism and the transatlantic slave trade. Their nation took cover and thrived incognito, ensuring that their country’s wealth of knowledge and resources were not pillaged and exploited by intruders. For the African diaspora, this is infinitely empowering. Having the chance to escape to a world where the power is in the hands of black people is exhilarating and inspiring, and I can only imagine the good it’s doing in the minds of young children of colour around the world.

Outside of Wakanda, Black Panther shows us a snapshot of a world that is all too familiar. A world that breeds hatred and the plot’s villains. Raised in California, Michael B Jordan’s character, Erik Killmonger, is a powerful reminder of the potential negative impact our prejudiced society can have on the oppressed. His character’s extremism is born out of a relatable rage against those who shipped slaves to America and a present-day system that repeatedly works against black people. I sympathised and cried with him, but I knew Killmonger’s anger was misdirected and now, thanks to Chadwick Boseman’s hero T’Challa, so will a young audience of black children. This film is more than an exercise in diversity for Hollywood, it’s a lesson on how to recover and move forward from society’s mistakes.”

__________________________________________________

February 16th – Loveless (2017), directed by Andrey Zvyagintsev

From David Sexton at the London Evening Standard:

“Andrei Zvyagintsev stunned Cannes three years ago with Leviathan, his film about overwhelming corruption and hopelessness in provincial Russia. Loveless, although turning away from politics, is an even bleaker indictment of a spiritual wasteland.

A handsome couple, Zhenya, a beautician, and Boris, a salesman, are divorcing and selling their flat in one of St Petersburg’s towerblocks. Neither of them want to take on their traumatised 12-year-old son Alyosha. Both are trading up. He has a younger, blonde girlfriend, heavily pregnant, clingy and scared. She’s delighted with her rich, hedonistic older guy.

As Zhenya and Boris row viciously, Alyosha screams silently, hiding in darkness behind a door. When he disappears, they don’t even notice for two days. The police are useless but a group of volunteers begin vigorously searching for him, combing the woods, finding a den he has shared with his one schoolfriend in a remote concrete ruin, some kind of abandoned hotel or club, an image in itself of total desolation. There is no resolution and Zhenya and Boris only turn on each other all the more savagely. She never loved him at all, she says, it was all a mistake, the boy should have been aborted. He agrees.

This Russia has the accoutrements of material prosperity — new cars, mobile phones, endless selfies — within the ugly superstructure left by the Soviet state, but no heart, no soul. Zvyagintsev shows us this with great formal clarity, a kind of mortified calm. In those woods, the trees are fallen, leafless and decaying. Loveless sets a high bar for the 70th Cannes Film Festival.”

__________________________________________________

February 16th – Western (2017), directed by Valeska Grisebach

From Michael Sicinski:

“Where John Ford set this trap in The Searchers by making John Wayne’s antihero a murderous racist, Grisebach is subtler and diagnoses her present moment to a fine point. Her lone-wolf figure, Meinhard (Meinhard Neumann), is merely a liberal, blinkered by assumptions he scarcely knows he has. So when he is on a job crew from Germany, stationed at the Bulgarian border to build a hydroelectric pump, he adamently rejects what he sees as the chauvinism of his fellow Germans, who keep to themselves and, in a crass move, fly the German flag from their campsite wall. Instead, Meinhard is going to go into the nearby village and try to get to know the locals.

This isn’t a huge stretch for Meinhard, who, we learn, has done time in the Foreign Legion. But this move sets Meinhard apart, since he is willing to struggle with those whose language he cannot speak, putting himself at a deficit of power. This, of course, is one of the tenets of good liberal behavior, and over the course of the film Meinhard is rewarded for it, not only through friendships and acceptance, but in more abstract ways such as tone, lighting, and framing. Grisebach makes it clear that he is our preferred point of identification. By contrast, Vincent (Reinhardt Wetrek), the job foreman, is repeatedly shown to be a cheat and a boor. His bullying interaction at the lake with local woman Viara (Viara Borisova) pretty much cements his status as a little man determined to seem big and bad.

In small, minor interactions, though, we begin to see Meinhard take liberties. At first, they are the sort that come along with not wanting to be taken advantage of, behaving as though he and the locals are on even footing and he is not a foreign patsy to be trifled with. But over time, as the villagers accept him, Meinhard starts to believe he has found the home that has eluded him throughout his life, and this is when he makes several strategic missteps. All the same, whether he had or not, Meinhard could be said to mistake hospitality for belonging, and in so doing he reveals himself to be far more presumptuous than Vincent or any other ‘rude’ tourist from the West.

Grisebach has brilliantly identified a continual human problem — the need to belong, to ‘be down,’ to be the one good guy who is accepted despite the sins of your own kind — and removed it from the classic ‘Cowboys and Indians’ template where, it should be said, it has become offensively simplistic, mixed up with overtones of Rousseau’s ‘noble savage’ myth. In Western, the question is not so much one of white privilege — all parties in the equation here are white — as it is one of East vs. West and the economic power that comes along with it. This is not to say that Grisebach is replacing raced or gendered power with class. But she is making a problem of structured oppression, one which also impinges on the emotions, something legible outside of kneejerk stereotypes. Because of this, Western can show us the problem of cultural appropriation as more than just a power move. It is also an act of misguided sincerity, a structure of feeling.”

__________________________________________________

February 18th – 24 Frames (2017), directed by Abbas Kiarostami

__________________________________________________

February 23rd – Game Night (2018), directed by John Francis Daley & Jonathan Goldstein

__________________________________________________

February 23rd – Annihilation (2018), directed by Alex Garland

From Justin Chang at The Los Angeles Times:

“Annihilation, a mind-bending foray into the unknown from the British writer-director Alex Garland, leaves you in an entrancingly beautiful daze. That may be an odd thing to say about a movie with mutant crocodiles, killer bears and an unflagging sense of menace, but for all its surface perils the picture also has a disquietingly serene core. It broods, stalks and sometimes pounces, but mostly — not unlike the five intrepid women who venture into its heart of darkness — it’s content to observe, almost as though it were studying itself through the lens of the camera. It gives itself, and the audience, an awful lot to see …

In confronting an extraterrestrial presence through the gaze of a human female, emphasizing her intelligence and composure while sneakily teasing out her emotional history, Annihilation at times suggests a more ferocious companion piece to Denis Villeneuve’s 2016 thriller, Arrival. It’s a connection that Garland reinforces aesthetically in the absorbing but unhurried pace established by Barney Pilling’s editing, the muted grays and sudden eruptions of color in Rob Hardy’s sun-streaked cinematography, and, above all, the pulsing, otherworldly drone of Ben Salisbury and Geoff Barrow’s score …

At first, the movie suggests an unusually cerebral variation on the doomed-mission template: Despite the actresses’ variable screen time, Rodriguez’s outspoken intensity, Novotny’s quiet sensitivity and Thompson’s riveting calm all register so vividly that you regret knowing some if not all of them will be eliminated. That’s not a spoiler; nor is it even half the story. With the exception of one genuinely breathtaking, blood-curdling ambush, Annihilation has little interest in the conventional mechanics of suspense and surprise, as evidenced by an array of flashbacks and flash-forwards that reveal at least one outcome of Lena’s journey (she lives!) in the very first scene.

Grounded by the grainy recurring image of a cell rapidly dividing, Annihilation is itself a fluid exercise in genetic mutation: It begins with scenes from a marriage, then quickly evolves into a wilderness adventure, an environmental horror flick and a striking depiction of physical and psychological entropy (emphasis on the ‘trippy’). Its most impressive achievement may be how easily it welds the mechanics of genre and the cinema of ideas. Garland’s movie has its grisly flourishes, but unlike so many thrillers that preoccupy themselves with spectacles of death, it’s more interested in pondering the strange, inextricable link between creation and destruction.”

__________________________________________________

March 9th – The Death of Stalin (2017), directed by Armando Iannucci

From Kenneth D.M. Jensen at Law and Liberty:

“What I expected beforehand was something like a full-blown comedy or at least a less-than-subtle farce. The New Yorker’s reviewer, Anthony Lane, made the disturbing suggestion that there was daring and genius in making evil funny. Yes, there is humor, but all of it is humor of a moment. Like much of the humor in movies and television, it’s easy, not daring: Just present a collection of evil men and women in power or hungry for it (or hungry to survive in life-threatening circumstances) as rubes and boobs like the rest of us. This, director Iannucci indeed does—particularly with Malenkov and Molotov, and also with lesser principals of the Communist Party’s Central Committee of March 1953. But that scarcely makes for a comedy or takes the edge off the horror of the film.

What I found compelling was the climate of fear it evoked and carried forward. We are let in on Stalin’s lists (followed by depictions) of condemned men and women being rounded up and executed. We see the anxiety of these people, who know that inattention in almost any circumstance could spell their doom. We see their dread of any word of theirs, spoken in even the most banal of circumstances, leading to their condemnation for simply being in the wrong place at the wrong time. While The Death of Stalin portrays Lavrenti Beria as the most evil of all (which certainly he was, besides Stalin himself), it does not omit the murderousness of the whole of the Party elite.

There’s a lesson here for those who imagine that one-party states, ideologues, and power-hungry, would-be tyrants by disposition are not really so different from ordinary politicians or even you and me. Struggles for power in such circumstances are all the same, irrespective of time and place. And they are both terrifying and disgusting. It’s matter of kill or be killed.

The film’s main point is that the death of Stalin brought on the ruin of his principal henchman, Beria—who perhaps in fact was even more evil than The Boss. Strange as it may seem, one can find present-day articles not only regarding Beria as Stalin’s most appropriate successor, but as the real “liberal” on the Central Committee, not Khrushchev. Of course, it’s a faulty comparison for Nikita was really no liberal. He simply played the same appearance-of-reform card that Beria would likely have played if he’d had the chance.

The Death of Stalin conveys the incredible vileness of the totalitarian regimes we fought against in the 20th century. Evil could be made universal indeed, as it trickled down from the top even unto sons or daughters of the condemned who felt compelled to turn in their parents to survive themselves. Men of any sort can evince the potential for evil implied in the notion of original sin. However, not all evildoers are equal. Some, like Adolf Hitler, Stalin, and Mao Zedong, were monsters beyond the imagination. Thus, the film shows, and begs us to countenance, the probable reappearance of more of them.

Accordingly, the virtue of The Death of Stalin is what it tells us about the greater evil of the individuals I just named, not simply the evil that resides in the heart of every man. These men, who largely ruled the people by giving them the choice of death or complicity in monstrous crimes in order to survive, are not, unfortunately, a dying breed. If I could, I’d compel younger folk inclined toward politics to go see it.”

__________________________________________________

March 10th – Thy Kingdom Come (2018), directed by Eugene Richards

__________________________________________________

March 16th – 7 Days in Entebbe (2018), directed by José Padilha

From Mark Tooley at Providence:

“After watching Seven Days at Entebbe Friday evening, someone behind me loudly remarked the film was very ‘evenhanded.’ Arguably it was, but dramatizations of hostage rescues from terrorists shouldn’t be so impartial. The Palestinian hijackers from the 1976 showdown at a Ugandan airport are portrayed sympathetically, having been victims of Israel as the Jews who created Israel were victims of Hitler, we are told. Their German Marxist collaborators are assisting them in the battle against imperialism.

Bizarrely, the film’s most stirring scenes, showing the rehearsal of the Israeli raid and the rescue itself, are cut short. We aren’t even shown the Israeli commandos liberating the hostages, instead only seeing their killing the captors. Prime Minister Rabin, ostensibly a dove, is shown advocating surrender to the hijacker demands for releasing imprisoned terrorists, while Defense Minister Peres defends Israel’s policy of no negotiations with terrorists.

The film, like nearly all movies, is historically fallacious. But there are titillating tidbits that recall the geopolitics of the 1970s. The hijackers tell the Air France passengers that France professed to be pro-Arab but sold arms to Israel and was complicit in repressing Palestinians. France was originally in the 1950s an Israel ally, partly due to its own colonial struggle against Arab nationalism in Algeria. After the 1967 Six Days War, France pragmatically shifted pro-Arab and sold arms to both sides. The film at least pays homage to the Air France crew that courageously declined release with other French passengers and remained with the Israeli and other Jewish hostages whom the terrorists retained.

Most sympathetically portrayed among the terrorists in the film is the male German Marxist hijacker, ostensibly an idealist publisher fighting the class struggle but anguished over the optic of Germans incarcerating and killing Jews. This subplot references the vast terror network of the 1970s and 1980s that bound together Palestinians with European Communists like the Red Brigades, Baader Meinhoff, and the IRA, with support from Kaddafi’s Libya and the Soviet Bloc.

There was also support from occasional African despots like flamboyant Ugandan dictator Idi Amin, whom the film accurately portrays as sadistically insane. After the Israeli raid, his soldiers murdered a hospitalized elderly Israeli woman left behind, along with her protesting Ugandan doctors and nurses. (The film doesn’t mention this atrocity and never shows the hijackers killing anybody.)

… There were Holocaust survivors at Entebbe, one of whom reputedly challenged his supposedly anti-Fascist Marxist German captor, who was somewhat flummoxed. (The film doesn’t show this incident, instead portraying the German comforting and hiding the Jewish identity of an elderly French Holocaust survivor.) Himself also mindful of the Holocaust, the Air France captain who led his crew in refusing to leave the Jewish captives, and who’s still alive at age 94, later recalled: ‘I joined de Gaulle’s free French forces in June 1943. I was 51-years-old at the time of Entebbe and I had been through the war. So I knew precisely what fascism was all about. I knew perfectly well what separation [of the Jews] meant and what it would lead to.’ He observed that an Israeli commando’s appearance before him at Entebbe ‘was as if an angel had come down from the sky.’

Seven Days at Entebbe spiritually fails because it doesn’t fully acknowledge what was obvious to the Air France captain, instead seeking moral equivalence amid banalities about peacemaking.”

__________________________________________________

March 16th – Journey’s End (2017), directed by Saul Dibb

From Adam Sweeting at The Arts Desk:

“There have been several film and TV versions of RC Sherriff’s World War One play since it debuted on the London stage in 1928, but Saul Dibb’s new incarnation, shown at London Film Festival, is testament to the lingering potency of the piece. Armed with a taut, uncluttered screenplay by Simon Reade and a splendid group of actors, Dibb evokes the terror and misery of the trenches without lapsing into preachiness or sentimentality.

Front and centre is Sam Claflin as Captain Stanhope, the much-admired commanding officer of an infantry company waiting nervously for an expected German onslaught. They know they’re a sacrificial gesture, under-manned and under-equipped but ordered to ‘hold them up as long as you can.’ Stanhope is on the brink of mental collapse, holding himself together with whisky but sticking it out because ‘it’s the only thing a decent man can do.’

Claflin’s staring-eyed desperation is agonising to behold (there’s a dream sequence where he stares, mesmerised, into a searing orange inferno). In contrast there’s Paul Bettany’s Osborne (or ‘Uncle’), a schoolteacher and family man who’s found a kind of Zen resignation. His benign concern for his men, including the impossibly green newcomer Lieutenant Raleigh (a baby-faced Asa Butterfield), is touching but futile. Toby Jones brings wry relief as Mason the company cook, fighting a losing battle against the uneatable, while Stephen Graham finds comradely warmth amid the gloom.

The rotting trenches and aura of apocalyptic breakdown rapidly vaporise Raleigh’s hero-worship of Stanhope (who’s engaged to his sister), and his first taste of action shatters his public-schoolboy illusions. Dibb has added just enough filmic scope to fill out the play’s contours without compromising the tightly-knit dramatic engine at its core. Excellent.”

__________________________________________________

April 6th – A Quiet Place (2018), directed by John Krasinski

From Bishop Robert Barron at Word on Fire:

“We flash-forward several months later, and we watch the Abbots (can the name have possibly been accidental?) going about their lives in what could only be characterized as a monastic manner: no conversations above a whisper, elaborate sign language, quiet work at books and in the fields, silent but obviously fervent prayer before the evening meal, etc. (I will confess that this last gesture, so thoroughly absent from movies and television today, startled me.) Given the awful demands of the moment, any gadgets, machines, electronic entertainment, or noisy implements are out of the question. Their farming is by hand; their fishing is done with pre-modern equipment; even their walking about is done barefoot. And what is most marvelous to behold is that, in this prayerful, quiet, pre-modern atmosphere, even with the threat of imminent death constantly looming, a generous and mutually self-sacrificing family flourishes. The parents care for and protect their children, and the remaining brother and sister are solicitous toward one another and toward their parents …

The central drama of A Quiet Place is that Mrs. Abbott is expecting a child. The entire family realizes, of course, that a wailing infant would, given the circumstances, mean almost certain death for all of them. And yet, they decide not to kill the child at his birth but to hide him and mute his cries in various ways. When so many in our culture are willing to murder their children for the flimsiest of reasons, when the law gives full protection even to partial-birth abortion, when people blithely say that they would never bring a baby into such a terrible world, the monastic family in this film welcomes life, even into the worst of worlds, and even when such an act is of supreme danger to them. As the baby is coming into the light, the mother finds herself alone (watch the film for the details) and in the most vulnerable situation, for one of the beasts has made its way into their house. As she labors to give birth, the devouring animal lurks. I was put immediately in mind of the scene in the book of Revelation, where Mary is in the throes of child birth as the dragon patiently waits to consume the child …”

__________________________________________________

April 6th – You Were Never Really Here (2017), directed by Lynne Ramsay

__________________________________________________

April 6th – Sweet Country (2017), directed by Warwick Thornton

__________________________________________________

April 6th – Lean on Pete (2017), directed by Andrew Haigh

From Tomas Trussow at Film Inquiry:

“The title of this film is ironic. Shatteringly so. It’s both the name of a quarter horse given a new lease on life by a sensitive teen named Charley (Charlie Plummer, in a beautiful breakthrough performance). It is also a philosophy, dusty and cloven of the fairy tales of yore, where companionate beings could serve as guides for the major transitions in life, standing firm with the child growing to become an adolescence, then an adult. Names and philosophies, however, are no longer enough when the fairy tale is decisively unmagical—nor even a fairy tale. Magic could ward off the pangs of loneliness. Lean on Pete wants us to know that such pangs are both unavoidable and necessary.

Andrew Haigh has been a refined voice for solitary souls in cinema for the past few years. His last film, 45 Years, was all about the oncoming chill of solitude when a wife realizes that she was not the only partner in her husband’s world. That, in effect, the love they shared was second-hand. Lean on Pete is his first American-set picture, located in the dusty plains of the Oregon High Desert, where loneliness is all but manifested in dryness, juniper and sage. His protagonist is his youngest subject yet, a boy who is soon bounced from his home after a tragic incident and must set off westward in search of the only other person willing to take care of him …

The inherently tripartite structure allows the film to respire on its own terms. Haigh never lets scenes dry up prematurely, or end on false notes. The editing is graceful, and Haigh’s camera unobtrusive, letting the action rise and fall naturally without the need for superfluous styling. This will inevitably bore some. That is understandable. Not all of us have the patience to sit in prolonged serenity. With Haigh, however, there are so many elements working together in tandem that, for me, I cannot tire of it. Even if it’s just Charley speaking plangently to his horse, the mise-en-scène still spreads toweringly over the frame, inviting both the rueful and the comforting to coexist, even for just one moment.

Haigh continues to be a treasure worth seeking, and Lean on Pete is one more example of his innate sense of precision and humanity. I feared that, by turning to an American setting and a neorealist vision, he would lose that simple poeticism that made Weekend and 45 Years so perfectly haunting. I was wrong. That poeticism has not left. One can even say that it has ripened and matured, and that it will continue to do so as he moves from strength to strength.”

__________________________________________________

April 6th – Pandas (2018), directed by David Douglas & Drew Fellman

From Peter Howell at the Toronto Star:

“They’re … the most endangered bear species on Earth, with fewer than 2,000 remaining in the wild in their native China, due to human destruction of their natural forest habitat. Efforts to increase that number is where the science kicks in for this absorbing film, which manages to pack a lot of information — and some real drama — into its 40-minute running time.

Directors David Douglas and Drew Fellman (Born to be Wild, Island of Lemurs: Madagascar), take us to the Chengdu Panda Base, where researchers have a successful breeding program that has increased the planet’s panda population by 200. But breeding pandas in captivity seems a lot easier than returning them to the wild, where they can fall prey to predators ranging from wild pandas to human poachers.

Enter Bi Wen Lei, a Mongolian researcher, and Jake Owens, an American conservation biologist. The two scientists use techniques learned from Ben Kilham, a New Hampshire black-bear rescuer known as ‘Poppa Bear,’ seen earlier in the film. The Imax camera follows the two scientists as they attempt to settle a female cub named Qian Qian into her new home in the mountainous wilds of Sichuan Province. A lot more effort is required than just pointing the way to the wild bamboo, the food staple that pandas consume 50 pounds of each day. Qian Qian has to be eased into her new environment, and there’s no guarantee she’ll safely settle in.”

__________________________________________________

April 9th – Chosen: Custody of the Eyes (2017), directed by Abbie Reese

__________________________________________________

April 13th – Beirut (2018), directed by Brad Anderson

From John DeFore at The Hollywood Reporter:

“A hostage rescue story set in the middle of the Lebanese civil war, Brad Anderson’s Beirut offers Jon Hamm as a different kind of persuasion merchant, trying to negotiate a friend’s release before more powerful men decide he’s not worth trying to keep alive. Increasingly tense and benefiting from a well-thought-out script by Tony Gilroy, it finds a slim opening for heroics in a place where all parties are tainted. Though not a sure thing commercially, it will play well with fans of John le Carre-sourced films.

Hamm’s Mason Skiles begins the film as a happy diplomat in 1972 Beirut, schmoozing with other Americans and confident he understands the messy politics of the region. But a shocking incident, which suggests he doesn’t know as much as he thinks, leaves both his life and his career a wreck. Ten years later, he’s a drunk earning a living by mediating labor disputes. He has a knack for seeing through each party’s bluffs and knowing what they’re willing to settle for once passions subside. What better place for him than back in the Middle East? …

Hamm is unsurprisingly excellent as a man whose intellectual gifts did not simply disappear when he started letting himself go. Though we’re set up to expect a bit more crafty deal making than the picture winds up delivering, Skiles’ long-overdue chance to confront the past offers enough emotional weight to make the war-zone detective work feel less formulaic than it might have. Pike’s role is considerably less rewarding.

Gilroy wrote this script in 1991, when it attracted interest but was considered too button-pushing to produce. Only after the success of Argo did this kind of story start to seem commercially viable again to backers. It’s rare to get such a dramatic flashback in the career of a filmmaker, but Beirut doesn’t feel like a leftover.”

__________________________________________________

April 13th – The Rider (2017), directed by Chloé Zhao

From Patrick Gamble at CineVue:

“A lot of has been written recently about the mindset of Middle America, with much of it reductive and defamatory. Here Zhao avoids politics as much as possible, instead rendering a mystical portrait of a region where community means everything and the corral holds an almost religious significance. An observational portrait of a secluded world that neither patronises its subjects, or romanticises their lives, The Rider is a mournful, yet transcendental film that merges the hard truths of documentary filmmaking with the poetic punctuation of fiction to create an alluring hybrid of the two.

Sadly some of this magic is dissipated by an overly prescriptive narrative, with Zhao shining her spotlight a little too brightly on Brady’s internal conflict, which in turn blinds the audience to the broader social context that dictate the world he inhabits. Thankfully the fleeting glimpses of the wider landscape are beautifully captured by director of photography Joshua James Richards, who makes the most of the natural light of the South Dakota wilderness, shooting as often as possible during the golden hour to create a series of unshakable images. The result is a topography that feels as if its constantly on the brink of revealing its secrets, with the grainy textures of Richard’s images feeling like he’s captured the unidentifiable mysticism that lingers in the dust.

Although Zhao’s film scores high on poetic imagery, she doesn’t skirt around the hard work and dedication Brady puts in to training horses. Some of the film’s best moments are those observing him as he breaks in foals, providing the audience with an insight into his methods while the camera’s inquisitive stare makes the trust that develops between man and horse the centrepiece of the film. This same degree of tenderness is also apparent in the scenes shared between Brady and Lane Scott; a friend and former mentor of Brady’s who ended up quadriplegic after a fall whilst bull riding. Now only able to communicate via hand signals, the pair sit silently as they revisit Lane’s former glory via YouTube clips and home videos. It’s a devastatingly tender scene, framing both men’s impossible dream of getting back in the saddle with the harsh reality that they’ll never ride again.

While many filmmakers attempt to give a voice to the marginal and ignored, few do so with the same artistic and sensitivity displayed here, with Brady’s reenactment of his own experiences providing an utterly convincing record of a young man re-discovering himself in a landscape that refuses to let him go. A deeply felt personal journey, the film shifts seamlessly from unflinching realism to a poetic expression of masculinity in crisis; crossing back-and-forth across the blurred boundary that separates art and reportage to create a totally unforgettable film about the bond between people and place.”

__________________________________________________

April 13th – Jeanette: The Childhood of Joan of Arc (2017), directed by Bruno Dumont

__________________________________________________

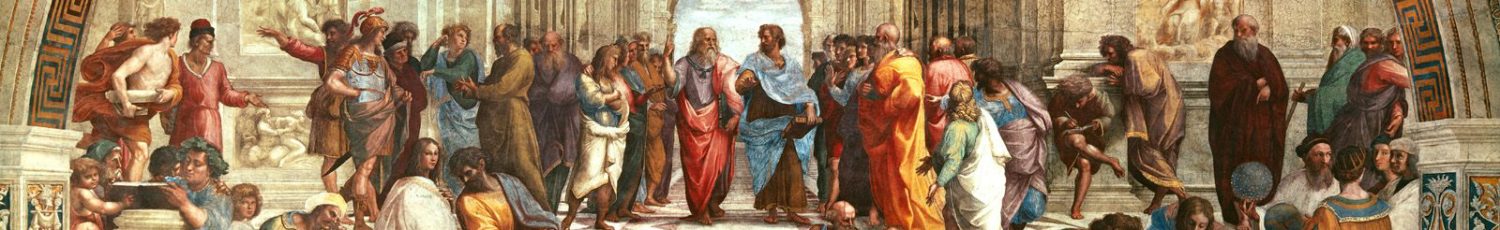

April 17th – Civilisations (2018), with Simon Schama, Mary Beard, & David Olusoga

From Henry Northmore at The List:

“In 1969 the BBC broadcast Kenneth Clark’s landmark series Civilisation, but unlike the corporations other great documentary series of the era (David Attenborough’s Life on Earth) they never really followed up on its success. Almost 50 years later Civilisations is inspired by Clark’s work but has an ever wider scope. The ‘s’ is important, whereas the original focused on Western culture, Civilisations aims to examine humanity through time and across the globe. It’s a hugely ambitious project with nine core episodes plus spin-off programming on TV, radio and even live events.

The first episode opens on a surprisingly political note with footage of ISIS destroying historic sites in Mosel and Palmyra, before Simon Schama looks at the dawn of culture from the oldest known decorated object (a piece of ochre found in South Africa dating back to a mind-boggling 77,000 BC), then heads on to Greece, Petra and the Mayan civilisations. In the second episode Mary Beard examines the representation of the human body in art and their place and meaning within society, starting with a huge stone head in Tabasco State, Mexico.

Each episode is a self-contained capsule of information presented by either Schama, Beard or David Olusoga. While Schama gazes in awe at prehistoric hand stencils and Beard delights in Greek ‘graffiti’ carved onto a statue in Egypt their sense of wonder is infectious. However, the show doesn’t just highlight the familiar touchstones of Greek, Roman and Egyptian culture, but also introduces us to Sanxingdui in China or Copán in Honduras, among many others.

Unsurprisingly, it’s a visual feast as the cameras sweep across ruined cities and townships or focuses in for tight close-ups to emphasis the exquisite details of relics, pottery and sculpture. Even more inspiring is the breadth of knowledge, beautiful nuggets of information and insights into ancient worlds. Accessible and intelligent, Civilisations conveys a message of globalism, revelling in the variety of our species’ ingenuity on an international scale. It’s more theory and presenter-led than the likes of Life on Earth or Blue Planet, and proves the human race is just as fascinating as the animal kingdom.”

__________________________________________________

April 27th – Avengers: Infinity War (2018), directed by Anthony & Joe Russo

From Steven D. Greydanus at National Catholic Register:

“Looking back, I find myself focusing on vanishingly brief moments of humanity, notably a pair of potentially important conversations between a man and a woman about their relationship: Tony and Pepper in New York; Vision and Wanda/Scarlet Witch in Scotland. Both conversations are rudely and quickly interrupted by extremely dangerous events, because this is a movie about a potential apocalypse and not about ordinary human life. But there it is: We need some sense of ordinary human life if the apocalypse is supposed to matter.

The scene with Wanda and Vision, in particular, is perhaps the most ordinary human moment in the film (prescinding from Vision being an artificial being). If there’s a moment in the film that says ‘Life is good,’ it’s this moment — and, in a movie with a villain eloquently articulating a compassionate case for wiping out half of all life in the universe, the counterproposal that life is good shouldn’t be taken for granted.

No relationship in the MCU is as vital and interesting as Tony and Pepper’s in the first Iron Man. (T’Challa and his sister Shuri in Black Panther come closest.) That so vibrant a ‘civilian’ as Pepper has been for years reduced to cameos (or, worse, temporarily infused with superpowers) is emblematic of why the small-screen approach doesn’t scale well to the big screen. On a weekly series, Pepper would be a regular character and her relationship with Tony would occasionally be at least the B-plot of an entire episode. A weekly series can vary between quieter, less eventful episodes and more high-impact episodes, each informing the other.

A tentpole movie, no matter how many Marvel cranks out or how long past two hours they run, has no time for that. Each installment is an Event, with big beats and (hypothetically) big stakes. (Spider-Man: Homecoming somewhat subverted the formula with a pleasingly smaller-scale story. Infinity War is the polar opposite, working the formula as it’s never been worked before.) Infinity War not only doesn’t make a definite statement; it hardly poses a question. Thanos has an idea, an ideology, but it’s barely challenged or cross-examined.

Perhaps the most important exchange occurs between Thanos and Gamora, whom he raised as his daughter after massacring her people. (By the end of the film it’s clear that Thanos is the de facto protagonist and his relationship with Gamora the defining relationship. There’s a flashback to Gamora’s childhood that probably should have opened the film.) Thanos argues that he saved Gamora since her people lived in desperate poverty — but Gamora insists that they were happy. To Thanos’ contention that universal overpopulation will lead to misery, Gamora says only, ‘You don’t know that.’ There’s nothing here like the elderly German defying Loki’s command to kneel in The Avengers or Cap rebuffing Loki’s worldview by alluding to his ‘disagreement’ with Hitler.

While the filmmakers work hard to balance the cast, some players are more crucial than others. In chess terms, Vision is the king and the Scarlet Witch perhaps the queen. After that, Thor and especially Doctor Strange stand out. On its own terms, Infinity War must be judged a success. That’s because the overriding creative priority is just like most Marvel movies: to make you want to see the next one. Mission accomplished — though I say it with a certain resentful irony.”

__________________________________________________

April 27th – Let the Sunshine In (2017), directed by Claire Denis

__________________________________________________

May 4th – The Guardians (2017), directed by Xavier Beauvois

Linda Marric, HeyUGuys.com:

“Director Xavier Beauvois (Of Gods and Men, 2010) is back again with a beautifully crafted production which tells the story of the women left behind in rural France after the of the majority of men of fighting-age were conscripted to fight in WWI. The Guardians (Les Gardiennes), takes a contemplative, slow paced look at the great war from the perspective of those whose stories are seldom told. Cannes Grand Prix winner Beauvois, offers a simply told and beautifully conveyed account of the devastating events which will eventually lead the way to the emancipation of women throughout Europe. Basing most of the action away from the battle ground, the director offers an alternative war movie, one where the fight takes place at home rather than on the battle field.

Adapted from Ernest Perochon’s 1944 novel, The Guardians spans two years in the lives of the women who inhabit Le Paridier, a family owned working farm run by Hortense (Natalie Baye), a resilient matriarch trying to make ends meet in the absence of her two sons and husband. While her daughter Solange (Laura Smet) does her part in running the farm in the absence of husband Clovis (Olivier Rabourdin), Hortence has to also make do without her school teacher son Constant (Nicolas Giraud), and his younger brother George (Cyril Descours) …

With long mournful scenes and slow meandering shots, the director forgoes the need for artifice in favour of natural storytelling and beautifully sedate exchanges between his characters. Baye is magnificent as Hortence, her quiet resolve and resilience are depicted with huge expertise and panache. The Guardians is a stunning production, which while not being entirely without fault, still manages to thrill and move its audience beyond all expectation. Beauvois is faultless in his ability to recreate the past, down to the last thread of every costume and every piece of equipment used on the farm. A genuinely astounding piece of filmmaking which is as beautiful as it is essential.”

__________________________________________________

May 13th – Little Women (2017), adapted by Heidi Thomas

From Hanh Nguyen at IndieWire:

“Set during and after the Civil War in Massachusetts, Little Women centers on the titular March sisters: responsible eldest daughter Meg (Willa Fitzgerald), tomboyish Jo (Maya Hawke), compassionate Beth (Annes Elwy), and the vain Amy (Kathryn Newton). When we meet them, they live in genteel poverty without much parental guidance because their pastor father (Dylan Baker) is off ministering to soldiers in the war and their mother Marmee (Emily Watson) has gone to him when he falls ill.

Unlike the shorter film versions of Little Women in the past, the PBS miniseries gives the story three whopping hours (split into one hour for the premiere and two hours the following week). Finally, the Marches’ story, which spans several years in the novel, gets the proper time to unspool and breathe at an unhurried pace, part of the reason for this version’s success. It is able to faithfully portray the majority of the sisters’ individual experiences, something that the past versions often had to truncate. The passage of time is felt, the nuances in interactions are more clearly portrayed, and characters have the time to evolve naturally. It also draws out far more humor than previous versions may have not had time to enjoy.

There’s not a weak link in the ensemble, beginning with the no-brainer casting of the great Angela Lansbury as the demanding Aunt March and Emily Watson as the warm and frazzled matriarch Marmee. Standouts also include Newton (Big Little Lies) who is the walking and talking embodiment of the impish, blonde-haired and blue-eyed beauty from the novel, and Jonah Hauer-King as the dimpled, charismatic rogue Laurie Laurence. Both bring just enough of devilish spirit and humor that it elevates their characters, who could come off as spoiled and petulant.

Ultimately, though, this is Maya Hawke’s vehicle, the first that she’s driven in her acting career on screen. And what a debut it is. Every production of Little Women hinges on who’s cast as Jo — whether it’s been June Allyson, Katharine Hepburn, or Wynona Ryder — to be the outspoken freethinker whose heart beats for her family and whose pen is poised to create genius. Jo’s early feminist spirit has always been the entrée for modern women into the Marches’ sphere. Her attempts to navigate what it means to provide for her family while steadfastly maintaining her independent ideals regarding relationships has fueled arguments for decades.

Hawke, who is the daughter of Uma Thurman and Ethan Hawke, simply dazzles. As Jo, she’s earnest, vibrant, and unselfconsciously coltish. Her direct gaze and husky voice are magnetic, and with this portrayal, it’s not hard to understand why Laurie is drawn to the animated and singular Jo, despite her every protest. The debate over that lopsided romance is one of the most enduring conversations about Little Women, with each new iteration attempting to shed light on Jo’s mental state and their dynamic. This PBS version has entered the fray in a way that may sway the opinions of longtime fans.”

__________________________________________________

May 18th – First Reformed (2017), directed by Paul Schrader

From Charles Ealy at Austin American-Statesman:

“Ethan Hawke stars as the lonely Rev. Ernst Toller, who presides over a historic but small Dutch Reform church in upstate New York. He and his wife are divorced, in part because he encouraged their son to join the military during the Iraq War – and their son was killed.

He’s grieving, and he spends a lot of his evening drinking and being self-destructive, even though he is supposed to be preparing for a celebration of the church’s 250th anniversary.

Then a pregnant parishioner (Amanda Seyfried) asks for the reverend to counsel her husband. The husband is a radical environmentalist and despairs over the planet’s future – so much so that he wants his wife to have an abortion, thinking that the world will be unlivable in 50 years.

Toller is strangely invigorated by the husband’s arguments, but this renewed vigor leads to a troubling flirtation with extreme violence …

As Toller, Hawke delivers a nuanced performance of a grieving, lonely man who’s searching for answers. Seyfried, meanwhile, offers a glimmer of hope as the pregnant Mary. And, yes, Schrader means for that name to have biblical implications.

For literary fans, Schrader also crafts a scene that’s an homage to Flannery O’Connor’s Hazel Motes of Wise Blood. And for fans of transcendentalism, there’s a levitation scene that’s mesmerizing.

First Reformed is an art movie, pure and simple. It won’t attract the teenage action-loving crowd. It won’t break any box-office records. But it’s beautiful, thoughtful and full of grace.”

__________________________________________________

May 18th – Pope Francis: A Man of His Word (2018), directed by Wim Wenders

From Steven D. Greydanus at the National Catholic Register:

A movie is only as good as its villain, and Wenders’ opening voice-over invokes nothing less than the problem of suffering and evil: natural disasters; terrorism and weapons of mass destruction; threats to the environment and extinction of species. Against this backdrop the ‘radical answers’ of these two men named Francis stand out with fresh urgency.

Neither the life nor the papacy of the former Jorge Bergoglio is Wenders’ subject. Instead, Pope Francis focuses on characteristic themes of his preaching and teaching — particularly those most accessible to viewers of any faith or of none — as well as the engaging personality and common touch with which he advocates them.

These include Francis’ advocacy for the poor, immigrants and refugees; the perils of consumerism and the problem of unjust distribution of wealth; stewardship of the environment and an integral ecology; the horror of war and international arms trade; and the importance of understanding and peaceful coexistence among the world’s religions.

Francis himself brings these themes to viewers, looking and speaking straight into the camera in excerpts of interviews shot for the film in various Vatican City locations, including the Vatican Gardens. Intercut with these interview clips are images from globe-hopping pastoral visits to the Americas, Africa, the Philippines and elsewhere, with the Pope interacting with children, prisoners, hospital volunteers, refugees and disaster victims. The flow of images is subtly enhanced by an unobtrusive string-based score (mostly bowed instruments with an occasional guitar).

As a final touch, Wenders highlights the Franciscan foundations of the Pope’s concerns with evocative footage shot to look like clips from some lost silent-era St. Francis movie that I now wish really existed. (Wenders cross-fades into the first of these clips, shot on a hand-cranked camera from the 1920s, from one of Giotto’s frescoes in the Upper Church of Assisi’s Basilica of St. Francis which the silent footage matches perfectly.)

Focusing on Franciscan answers to global problems means, on the one hand, that Pope Francis is wholly positive in tone. Whatever tensions exist between Francis’ message and his personal failings, or whatever stumbles, gaffes or controversy have marked his papacy, are beyond the scope of Wenders’ interest …

More than once we see tears on people’s faces — and, while one might suspend judgment at the sight of a politician brushing away a tear as the Pope addresses a joint session of Congress, tears on an inmate’s tattooed face as Francis embraces and preaches to prisoners or washes and kisses their (also tattooed) feet on Holy Thursday are another matter.

The mystery of suffering and evil looms above all in a 2014 papal visit to the Yad Vashem Holocaust Memorial in Jerusalem and a 2015 multireligious gathering at Lower Manhattan’s 9/11 Memorial.

Similarly, in pastoral visits to a volunteer-run hospital in the Central African Republic, a typhoon-devastated Philippines and a refugee camp at the Greek island of Lesvos, Francis’ active solidarity with those who suffer evokes, however dimly, the Crucified Jesus to whom he pointed when asked about the problem of evil …

If Pope Francis: A Man of His Word isn’t the documentary final word on the 266th pope, in a way it’s something better: It’s a winsome, challenging call to take the Gospel more seriously and to work to make the world around us a little bit better.”

__________________________________________________

May 19th – Fahrenheit 451 (2018), directed by Ramin Bahrani

From Matt Zoller Seitz at Vulture:

“This is a highly idiosyncratic and personal adaptation of a classic science fiction novel, more temperamentally aligned with brainy, slightly chilly science fiction films like The Day the Earth Stood Still, A Clockwork Orange, Gattaca, and Ex Machina than dystopian epics that lean on scale and mayhem. It should also be considered one of the key pop culture works of the Trump era. It speaks directly to the persistent cultural conditions (chiefly anti-intellectualism) that made Trump possible, as well as to the sorry state of the country at the time of the film’s release.

Bahrani began adapting Bradbury’s novel in election year 2016, and shot it (with Michael B. Jordan as Montag and Michael Shannon as his boss, Captain Beatty) in 2017. It feels timeless, but also very much of-the-time. More so than Francois Truffaut’s 1966 version of Fahrenheit — which seemed to get so tangled up in translating a French New Wave filmmaker’s sensibility to the Hollywood system that it never attained a personality of its own — this Fahrenheit is distinctive, so on-message from one moment to the next, and so scary in both its depictions and implications, that there are times where it feels as if it’s intellectually brutalizing the audience, slapping viewers across the face to get them to wake up from a stupor.

The first third of Fahrenheit plunges us eyeball-deep into the mind-set of American fascists, good soldiers who believe deeply in their mission to crush dissent and homogenize society intellectually since they can’t homogenize it culturally. The fully indoctrinated and wildly enthusiastic Montag roasts books and brutalizes citizens in order to demonstrate that he’s absorbed the values of his supervisor and surrogate daddy, Beatty, who raised him from childhood after Montag’s father died. The circumstances of that death (and the fate of the rest of his family) are a bit fuzzy, and they only gain a wee bit more clarity as the film goes on because Montag is recalling them through a haze of memory-weakening, defiance-sapping pharmaceuticals delivered via eyedrop (a great touch that connects reading and watching).

Although it’s set in a mid-sized Ohio city, it depicts a physical world that’s merely an adjunct to the virtual one that dominates people’s waking life and feeds them approved thoughts. The old days are described as unruly, an intellectual wild west in which books and publications could say almost anything they wanted, and people argued about ideas. This, Beatty tells Montag, is how they ended up in a second civil war that killed 8 million Americans, including Beatty’s own father. In order to prevent more wars, Beatty says, society must become monolithic, waging constant war against ‘eels’ (short for ‘illegals’). Bahrani avoids allowing this sentiment to lapse into such vagueness that anyone can treat Fahrenheit as their own personal self-justifying metaphor: the film makes it clear that the ruling class has drawn self-interested conclusions and acted accordingly, and that the values of Beatty’s bosses are strictly monocultural, that no dissent is allowed here, and those with physical limitations or deformities (such as the two blind people and a citizen with Down syndrome shown huddled in an abandoned building) are not welcome in broad daylight. Unauthorized writing is called ‘graffiti,’ and holding it, circulating it, or uploading it to the official state-run internet (called the Nine) is a crime. The number of languages actively spoken in around the world has been reduced from hundreds to 16. The plan, whatever it is, appears to be working …

Fully half the lines out of Shannon’s mouth are aphorisms that could be printed on an Inspirational Quote of the Day calendar marketed to sadists who worship power. (‘If you don’t want a person to be unhappy, don’t give them two sides of a question to worry about,’ Beatty tells the troops.) The burning of books is treated as the visually arresting cornerstone of a larger project to defoliate or destroy the historical memories of Americans, and make them fear and loathe any thought not served up by the government and the corporate media (depicted here as cheerleaders for the state). The movie makes the same argument in favor of a robust and humanistic culture that A Clockwork Orange makes for the necessity of free will: It may produce some bad results, but it’s still vastly preferable to the alternative. A handful of colors predominate: inky black, flame orange, puke green, and police-light red and blue, the colors of a nation that demonizes intellectuals and education, is fueled by fear, and nakedly worships power and cruelty. This society not only refuses to entertain anti-authoritarian sentiments, it makes reality TV-style superstars of skull-cracking cops like Montag and Beatty, and broadcasts their adventures on video screens throughout the city, including gigantic ones plastered across the faces of skyscrapers. As one character casually mentions, in the time ‘before bots and automated writing … nobody was reading any more, or they were just glancing at headlines generated by an algorithm.’ That time sounds like the time we’re in right now. Bahrani is showing us is where he thinks we’re headed.”

__________________________________________________

May 25th – Summer 1993 (2017), directed by Carla Simón

__________________________________________________

May 26th – The Tale (2018), directed by Jennifer Fox

From Josh Martin at Film Inquiry:

“Directorial debuts are a dime a dozen at Sundance, but this one (the narrative debut of a documentary filmmaker) felt different. From the outside looking in, Fox‘s examination of her own sexual abuse as a young girl seemed like a necessary, powerful statement in the midst of the #MeToo movement. When you consider the fact that Harvey Weinstein preyed on his victims at festivals like Sundance, the weight and gravity of Fox’s achievement becomes even more significant.

Picked up in a high profile deal, The Tale ended up selling to HBO Films in lieu of a major theatrical release. While Fox‘s film may be shut out of the awards race, the medium does not dilute the gut-wrenching power of this story in any way. The film, which premiered on May 26 on HBO, is a difficult and uneasy viewing experience, one that is never content to deal with sexual assault and rape in an abstract sense. Fox confronts the abuse she suffered in a direct and pointed manner, digging deeper into her own past before exposing a cycle of pain that has continued throughout her own life.

In an unconventional fictionalization of a personal story, Laura Dern plays Fox, the film’s very own writer and director. She’s a documentary filmmaker, but her life takes a surprising turn when she discovers an old story from her middle school years. Her mother (Ellen Burstyn) discovered this account of Jennifer’s relationship with an older man, and she’s utterly distraught by this depiction of abuse. Intrigued by this chronicle, Fox begins to dig into her own personal history to find the truth.

What she finds is undeniably terrible, a lifetime of ripple effects from two relationships where she was taken advantage of repeatedly. The abusers were Mrs. G (Elizabeth Debicki) and Bill (Jason Ritter), two coaches with a knack for making young Jenny feel loved and appreciated during her tumultuous home years. As she tracks down those who abused her and those who could have known, Fox comes to terms with what happened to her, uncovering the lies she was told by others and those she told herself. And in the process, she finds strength in the way she survived and overcame this horrific tragedy.

With repetitive sequences, poetic interludes, and plenty of fourth-wall breaks, The Tale makes a personal story feel even more immediate. At times, Fox‘s approach almost feels more suited to the theatrical treatment, as I can imagine a director using both sides of a stage to present the contrasting narratives. But in cinematic form, the chosen devices and quirks of the story never feel gimmicky. Instead, they serve the characters in a moving and striking way, adding to the conversational tone and astonishing intensity of the film.”

__________________________________________________

June 8th – Won’t You Be My Neighbor? (2018), directed by Morgan Neville

From Josh Terry at the Deseret News:

“Morgan Neville’s documentary is everything you’d want from a profile on the man behind the longtime PBS television program Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood. It’s insightful, charming, thoughtful and compelling. The documentary, which premiered at this year’s Sundance Film Festival, opens with a piece of grainy, behind-the-scenes black-and-white footage from 1967. Seated behind a piano, an impeccably clean-cut Rogers shares the mission statement for his career: to ‘help children through some of the difficult modulations of life.’

Rogers insists that love is the motivation behind all of his work, and based on the evidence in Neville’s film, it’s easy to believe him. Neville picks up Rogers’ story as the lure of television sidetracked him from his original plan to become a Presbyterian minister. Convinced the medium had powerful potential for good — and disgusted by the clowning antics he saw on TV at the time — Rogers started working on a show called The Children’s Corner and eventually launched Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood in 1968.

Won’t You Be My Neighbor? shows us how different signature items for the show — including Rogers’ trademark sweaters and sneakers — were worked into the program and shares the inspiration behind elements such as the Neighborhood of Make-Believe. Along the way, Neville paints a compelling portrait of one of the most truly unique personalities to grace the television screen. We see Rogers’ sincere love of children, but we also see how certain parts of the show were an extension of his own fears and weaknesses. (His wife, Joanne, explains that of all the characters on the show, the puppet Daniel Tiger was the one who spoke most directly for her husband.) …

We also get a glimpse of how Mister Rogers’ Neighborhood tried to respond to current events, such as the assassination of Sen. Robert Kennedy in 1968 or the Challenger explosion in 1986, and the film even delves into questions of whether Rogers was gay (he wasn’t) or a former Navy SEAL (he wasn’t).

Interviews with Joanne, Rogers’ sons and co-workers — including Francois Scarborough Clemmons (who played Officer Clemmons) — reaffirm that Rogers was every bit the unique personality off camera as he was on camera. Neville does a solid job of striking an important balance between being inquisitive and respectful, which keeps Won’t You Be My Neighbor? from becoming a gushing tribute or a cynical hit piece.”

__________________________________________________

June 8th – Ocean’s 8 (2018), directed by Gary Ross

From Peter Sobczynski at eFilmCritic.com:

“Of course, the big appeal of Ocean’s 8 is to see the members of its female-centric cast strutting their collective stuff in roles that, often as not, allow them to goof off of their various public personae. Indeed, some of the best parts of the movie are the ones that feature them together and sparking off of each other. In her first film in quite a while, Sandra Bullock proves to be entirely winning as the ringleader of the gang and Blanchett is just as entertaining in a part that is roughly equivalent to the one that Brad Pitt played in the earlier films. Carter is hilarious as a character who was the hot name thirty years ago but who has been cast aside with the shifting cultural tides. As for Rihanna and Awkwafina, they may not have the years of acting experience that their co-stars have racked up but they both have the kind of pure personality that allows them to more than hold their own against them. The best of the bunch, however, is Hathaway, who steals the film outright by deftly spoofing her own image as Daphne, who maintains virtually every real and imagined bad habit that a rich and popular young actress could be accused of having but who nevertheless proves to be a lot smarter and cannier than anyone could imagine. (There are also a number of entertaining cameo appearances as well but whether any of them are done by members of the previous Ocean’s films is something that I leave for you to discover.)

Of course, the world that Ocean’s 8 is being released in is a far different one than the one that existed when it began production. Then, the biggest concern might have been whether the notion of an all-female take on Ocean’s 11 would run into the same buzzsaw that the Ghostbusters remake did … Now, coming in the wake of the MeToo movement, there is the chance that it will have sociopolitical concerns ascribed to it that no one could have dreamed of when it went before the camera. On the one hand, this would be a bit silly because this is a film that is as much of a fantasy in its own way as the superhero movie of you choice and to pin real world concerns upon it would be absurd. At the same time, however, it does, even if inadvertently, tap into the anger and energy driving that movement in the way that it embraces its female-centric perspective without ever making apologies for not having any substantial male characters of note. Intentional or not, Ocean’s 8 is clearly a movie custom-made for this particular point in time — thankfully, it also happens to be a hugely entertaining and eminently watchable one as well.”

__________________________________________________

June 15th – Incredibles 2 (2018), directed by Brad Bird

From Roger Moore at Movie Nation:

“In Incredibles 2, the villain is named ‘The Screenslaver,’ a monster straight out of the American Id, as relevant as each day’s latest panic-stricken headlines.

Screenslaver has identified our weakness — ‘screens,’ that we ‘don’t talk. You watch talk shows. You don’t play games, you watch game shows.’

And another Achilles heel — ‘People will trade quality for ease every time.’

People have ‘less trust in Congress’ to do the right thing ‘than monkey’s throwing darts.’

When Elastigirl, Mrs. Incredible, figures all this out, she announces ‘We’re under ATTACK.’ And in the cartoon America, at least, people hear her.

Incredibles 2 is a superhero action comedy that’s about something, and when’s the last time the moneychangers at Marvel could make that claim? Writer-director Brad Bird has loaded a noisy, long and daffy farce with the most potent Pixar political message since Wall-E.

‘Screens’ are a threat to our freedom.”

__________________________________________________

June 29th – Leave No Trace (2018), directed by Debra Granik

From Christina Newland at MUBI:

“America has always been too vast of a nation to account for all those who willingly go off the grid; in its thickets of forest and endless plains, there are bound to be a few who move to the margins and live off the land, in the great rugged individualist tradition. Be they the rural homeless, ardent survivalists, or various drifters, they isolate themselves from the mores of traditional housing and government rule.

Leave No Trace, Debra Granik’s latest feature, is about just such a pair of people. Will (Ben Foster) and his teenage daughter Tom (Thomasin McKenzie) live a solitary, tightly-knit lifestyle in a national park outside Portland, where their home is a tent and Tom learns a variety of outdoor skills in order to be self-sufficient. Will is a bearded ex-military man with a pool of unknowable despair behind the eyes, but he’s a loving father and the center of Tom’s life. Unmoored from school, community, and wider society, Tom and Will cling to each other even when they are forced off of public land by police and attempt to adjust to an entirely different home. But Will is a broken man—almost monosyllabic with even the kindest strangers, and marked with PTSD that seems to manifest itself most as a paranoiac restlessness.

Granik’s unhurried, deeply naturalistic approach sees her camera linger on the careworn faces of army vets and RV park tenants, and on the wide green canopies of the Pacific Northwest. She’s intent on showing the remarkable kindness of the folks that father-and-daughter encounter on their travails: truck drivers who insist on checking the well-being of their hitchhikers; beekeepers willing to entertain a kid’s curiosity; fellow veterans who offer medical help to their compatriots both physical and mental.

This homespun sensibility is never overplayed, but sees an essential goodness in blue-collar middle America that is notable for its nuance. The film is not explicit about the politics of these marginal Americans—but it doesn’t take much imagination to work out. Will’s ex-military survivalism seems pretty strident, yet he—like all the others—exists outside the realm of the political.”

__________________________________________________

June 29th – Custody (2017), directed by Xavier Legrand

__________________________________________________

June 29th – Woman Walks Ahead (2017), directed by Susanna White

From David Crow at Den of Geek:

“With a deft hand and a large reserve of ambition, director Susanna White mounts a very elegiac vision with Woman Walks Ahead, one in which she and star Jessica Chastain contribute to the growing subgenre of deconstructionist oaters. Within the familiar form of ‘Cowboys and Indians,’ they acutely assess the role of women in this well-worn cinematic genre, as well as the eternal tragedy of Native American relations in American history. While some have argued Woman Walks Ahead is a white savior movie, the sorrowful awareness of the film is that it knows all too well about its privilege, and the pain such good intentions can still inflict from 1890 to 2018.

If you’re familiar with the story of the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation, then the setting of 1890 has a special meaning when the film begins. It is in this context that Chastain plays the real-life artist Catherine Weldon. Although highly fictionalized for the film, Chastain’s character does capture the startling (and eponymous) audacity of Weldon, who despite being born into affluent New York society used the new freedom afforded by her husband’s death to travel to Dakota in an effort to paint a portrait of Sitting Bull, the legendary Lakota Chief and last surviving warrior to lead the defeat of Lt. Col. George Custer almost 15 years earlier. Yet nothing is quite how Catherine imagines it when she steps off the train.

Rather than a lush land of noble and idyllic Natives, Catherine finds herself unwelcomed and uninvited at nearly every turn, including by Col. Silas Grove (Sam Rockwell), who urges Catherine to never exit the locomotive. When she does, she is immediately spat on by white locals who despise word of an eastern agitator who’s come west to ‘help’ Sitting Bull; she is robbed, stranded in the wild, and soon ordered by the local government agent (Ciarán Hinds) to immediately depart on the following morning’s train. And even the American Indians she so romanticizes aren’t exactly receptive. After all, she meets the storied Sitting Bull (Michael Greyeyes) not as the buckskinned and feather adorned warrior, but as a weary and articulate English speaking potato farmer. (He demands compensation before he agrees to have any talk of portraiture.) …

Sitting Bull and Catherine form an unlikely friendship due to both being marginalized, which for the most part is slowly earned and beautifully played by both Greyeyes and Chastain. Presumably, White and screenwriter Steven Knight (Eastern Promises) would’ve been happy to make a film strictly about the late life and death of Sitting Bull, and the consequences that followed. However, the feminist entry-point into the story from Catherine’s perspective is more than just a commercial concession; it’s also a self-conscious opportunity to explore the limits of the ‘white savior’ narrative.

There is a strong feminine underpinning to Catherine’s journey, which was in reality then (and still would now) be considered fairly radical, as she goes from Brooklyn patrician to political activist working on behalf of the Lakota Reservation, which is being ‘presented’ with an unfair land grab deal via the Dawes Act. Even so, her alliance with Sitting Bull is not a thing of pure righteous tact or political shrewdness. There is a thematic consideration of the failure of well-meaning voluntourism, as despite Catherine’s virtuous cause, she is entering a political tempest in a rowboat and with no idea which direction land resides … The truthfulness about its own blindspots gives Woman Walks Ahead a startling clarity, as well as the ability to paint Greyeyes’ Sitting Bull in more than the traditional cinematic broad strokes.”

__________________________________________________

July 6th – Ant-Man and the Wasp (2018), directed by Peyton Reed

From Kyle Smith at National Review:

“Scott Lang (Paul Rudd, who is also one of the five screenwriters credited) is after his previous capers a few days shy of serving out a two-year sentence of house arrest monitored by ankle bracelet. A dream introduces Scott to Janet (Michelle Pfeiffer), the disappeared wife of his former mentor Dr. Hank Pym (Michael Douglas). She was lost for 30 years when, while saving thousands disarming an inbound missile, she went from insect-sized to “sub-molecular” — a one-way journey to a sci-fi netherland called the ‘quantum zone.’ Much highly technical discussion about the details ensues. Scott: ‘Do you guys just put ‘quantum’ in front of everything?’

The upshot is that Scott is a conduit to Janet’s thoughts (Rudd gets to pretend he is Pfeiffer for a while), through which she can help Hank and his daughter Hope (Evangeline Lilly), now tricked out with a flying version of the Ant-Man suit, bring back Janet from the quantum zone. Villainy stands in their way, however: A sleazy restaurateur/black marketer (Walton Goggins) keeps stealing Hank’s laboratory building. Hank has unwisely shrunken it down to the size of a wheelie bag, which makes it really quite easy to steal …

The climax follows the same toddler-empties-toybox model of a lot of other Marvel movies: Some things get massively inflated, some stuff gets shrunk, and back and forth and round and around, amid lots of hectic racing around San Francisco. In the midst of all this, the priceless Michael Peña, who plays Scott’s pal and should be in every movie, keeps things grounded by channeling the audience’s boyish wonder (‘I wish I had a suit,’ he says). Also, there’s a giant Pez dispenser used as a weapon. When a villain makes an inexplicable sudden getaway via ferry, Scott wonders, ‘How did he even have time to buy a ticket?’ It’s the kind of thing I always wonder, too, and the wry self-questioning of its own contrivances makes the film impossible not to like.

So Ant-Man and the Wasp is worthwhile, if not a must-see, appealing less for its thundering action than for its throwaway gags. By the end there’s a suggestion that Pym’s gift for shrinking and enlarging could lead to a triumph over one of the most implacable scourges imaginable; he and his ladylove take a townhouse the size of a box of Triscuits out of their gear, pop it on the beach, and then blow it up to normal townhouse size.

Presto, but of course the enemy will not be denied a response. So I look forward to the next chapter, Ant-Man vs. the San Francisco Zoning Regulations.”

__________________________________________________

July 6th – Sorry to Bother You (2018), directed by Boots Riley

__________________________________________________

July 13th – Eighth Grade (2018), directed by Bo Burnham

__________________________________________________

July 20th – Generation Wealth (2018), directed by Lauren Greenfield

From Rich Cline at Shadows on the Wall:

“Filmmaker Lauren Greenfield takes her fabulous doc The Queen of Versailles and spirals out to explore the much bigger picture, creating one of the most vital, urgent films in years. An expertly assembled documentary packed with striking imagery, it’s also a riveting exploration of consumerism, taking a surprisingly personal approach that touches on unexplored aspects of a society that’s addicted to monetising virtually everything.

As she looks back at her 25-year career, Greenfield sees a connecting theme in her photographs and films: the obsessive craving for more of everything. This need for wealth isn’t just about money, it’s an addiction that includes sexualisation and body image issues. Has the American dream turned into a fictionalised depiction of who we wish we were, pretending to live a life that we know we can’t afford and to be someone we aren’t? The fallout here includes crippling debt, crumbling bodies due to surgery and collapsing families.

The point is made that all civilisations, as they begin to decline, flame out in a flamboyant display of excess. But Greenfield isn’t pointing fingers here; she explores her own workaholic tendencies even as she weaves her husband (producer Evers) and sons (teens Noah and Gabriel) right into the core of the film. She also tellingly interviews her parents (Patricia and Sheldon) and revisits subjects of her earlier work, which allows her to include staggering narratives that span decades, each adding a telling angle to the overall film …