Hermeneutics: My First Step into the Catholic Church – Part II, On Metaphysics

“The authority of holy Scripture says, on those points on which it would inform us, some things so plainly and clearly even to those who are utterly void of understanding, that not only are they not veiled in the obscurity of any hidden meaning, but do not even require the help of any explanation, but carry their meaning and sense on the surface of the words and letters: but some things are so concealed and involved in mysteries as to offer us an immense field for skill and care in the discussion and explanation of them.”

– John Cassian

“Thus is it that, in a wonderful manner, all of Sacred Scripture is so suitably adjusted and arranged in all its parts through the Wisdom of God that whatever is contained in it either resounds with the sweetness of spiritual understanding in the manner of strings; or, containing utterances of mysteries set here and there in the course of a historical narrative or in the substance of a literal context, and, as it were, connecting these up into one object, it binds them together all at once as the wood does which curves under the taut strings; and, receiving their sound into itself, it reflects it more sweetly to our ears — a sound which the string alone has not yielded, but which the wood too has formed by the shape of its body. Thus also is honey more pleasing because enclosed in the comb, and whatever is sought with greater effort is also found with greater desire. It is necessary, therefore, so to handle the Sacred Scripture that we do not try to find history everywhere, nor allegory everywhere, nor tropology everywhere but rather that we assign individual things fittingly in their own places, as reason demands. Often, however, in one and the same literal context, all may be found together, as when a truth of history both hints at some mystical meaning by way of allegory, and equally shows by way of tropology how we ought to behave.”

– Hugh of Saint Victor

_________________________________________________________

The first part of this essay was published on May 18, 2019, entitled “Hermeneutics, My First Step into the Catholic Church – Part I, On Preunderstanding.” It ended by asking the following question:

When there are competing traditions of interpretation of Scripture, how does one choose from among them?

Asking this question now presupposes a great deal that we have carefully worked our way through in the first essay, including the facts: (1) that interpretation is an unavoidably necessary practice of everyday life; (2) that our perception of reality is made possible by, and shaped by, our memories and experiences, which in turn makes the forming of concepts possible; (3) that there is a debate in epistemology over whether the use of memory and experience is necessary for rational thought; (4) that we each have a body of assumptions which we bring to our perception and interpretation of reality, and this is called a preunderstanding; (5) that hermeneutics is the art or science of interpretation; (6) that there is a rules-based hermeneutics that presupposes the existence of objective truth; (7) that the distinction between exegesis and eisegesis in interpretation often presupposes the rationalist school of epistemology; and (8) that there are, therefore, different traditions of interpretation depending upon different preunderstandings and different schools of epistemology.

All these propositions put together can seem a bit intimidating. But it is important to keep reasoning our way forward, and there is a payoff that makes doing so worth the effort. Our next steps can be understood by anyone, and I will keep these ideas as simple and as clear as possible.

Epistemology determines what one believes regarding what it means to know something and what is possible to know. In other words, your epistemology determines what you believe about the knowledge of truth. While there are disagreements within epistemology, every viewpoint can still be logically categorized into a limited number of schools of thought. No matter the source that one believes knowledge comes from, if questioned, one would be forced to admit that knowledge originates either from the senses or from reasoning. Empiricists hold that knowledge derives essentially only from the senses. Rationalists hold that knowledge derives essentially only from reasoning. Realists hold that knowledge derives from both the senses and reasoning combined together. What you believe about this will predispose what you believe concerning the interpretation of Scripture and of reality itself.

Now, there is another angle of looking at these same questions, and that is from the angle of what is called metaphysics. Just as everyone cannot help but assume an epistemology, so everyone cannot help but have a metaphysics. Metaphysics is one’s viewpoint regarding the nature of reality and what it means for something to be real. Your metaphysics therefore determines a great deal about how you live, because you have to make assumptions about what is and what is not real in the world around you in order to act within it. In early times, metaphysics was often explained by what is called “the problem of universals.” The problem of universals is an old debate about what reality consists of, namely, universals and particulars. A particular is an individual thing, fact, or detail. A universal is a property, trait, or characteristic shared by a collection of particulars.

Now, there is another angle of looking at these same questions, and that is from the angle of what is called metaphysics. Just as everyone cannot help but assume an epistemology, so everyone cannot help but have a metaphysics. Metaphysics is one’s viewpoint regarding the nature of reality and what it means for something to be real. Your metaphysics therefore determines a great deal about how you live, because you have to make assumptions about what is and what is not real in the world around you in order to act within it. In early times, metaphysics was often explained by what is called “the problem of universals.” The problem of universals is an old debate about what reality consists of, namely, universals and particulars. A particular is an individual thing, fact, or detail. A universal is a property, trait, or characteristic shared by a collection of particulars.

It is sometimes difficult to explain how important these issues still are. The problem of universals is not a debate that has become outdated and irrelevant. Today, with our focus on successfully pursuing and acquiring a practical education, a college degree, a career, a family, and a retirement, any talk about metaphysics often sounds impractical or abstract. Different writers have tried to explain why these questions matter with varying persuasiveness. Yet how we answer “the problem of universals” has far reaching consequences, not only in our religious beliefs, but also in our politics, our local community, our environment, our history, our laws, our wars, our governance, and our international relations. Historian Charles Homer Haskins tried to express this when he wrote of the different schools of metaphysics:

And if the differences often seem minute or unreal to our distant eye, we can make them modern enough by turning, for example, to the old question of the nature of universal conceptions, which divided the Nominalists and Realists of the Middle Ages. Are universals mere names, or have they a real existence, independent of their individual embodiments? A bit arid it all sounds if we make it merely a matter of logic, but exciting enough as soon as it becomes a question of life. The essence of the Reformation lies implicit in whether we take a nominalist or a realist view of the church; the central problem of politics depends largely upon a nominalist or a realist view of the state. Upon the two sides of this last question millions of men have “all uncouthly died,” all unconsciously too, no doubt, in the majority of cases, unaware of the ultimate issues of political authority for which they fought, but yet able to comprehend them when expressed in the concrete form of putting the interest of the state above the interest of its members.

Given the consequences and the great conflicts in history resulting from disagreements over metaphysics, we should certainly care about this. So how what would be one of the simplest ways of explaining the different viewpoints in metaphysics?

The Problem of Universals & the Major Schools of Thought in Metaphysics

Just as with epistemology, there is a wide variety of disagreement within metaphysics. But we can still order how we survey the subject. Every single metaphysical viewpoint can be categorized into one of three initially defined schools of thought. The first thing that will help us to understand the spectrum here is to see that these schools of thought depend upon a number of distinctions about what really exists. Metaphysics is the reason why distinctions have been made between mind and matter, spiritual and physical, immaterial and material, ideas and individuals, concepts and things, and universals and particulars. The various disagreements about what, among these distinctions, can and cannot be considered to exist have been argued throughout history. For our purposes, it will help us to focus upon (1) mind and matter, and (2) universals and particulars. This results in everyone being categorized into one of the following metaphysical schools of thought:

Nominalism: only particulars exist (in matter), universals do not exist

Realism: both particulars and universals exist (in mind and in matter)

Solipsism: only universals exist (in mind), particulars do not exist

The least prevalent of these three viewpoints, solipsism, has been argued for by some ancient Greek sophists (like Gorgias), by some teachers of Hinduism, and by some practitioners of what is called “New Age” spirituality. Yet solipsism is not often seriously maintained, partly because it is both impractical and dull, and partly because anyone who really believes in solipsism will not be someone who has motivation to talk about it. Solipsists are not generally doctors, lawyers, soldiers, scholars, engineers, mathematicians, pilots, mechanics, plumbers, electricians, pharmacists, or any other profession involving the hard work of scholarship, public service, or the trades. It is possible that solipsists might go in for politics, acting, marijuana cultivation, televangelism, or vagrancy but they are consistently not interested in promoting, let alone in discussing, metaphysics. This leaves us with realism and nominalism.

There are, of course, variations of both. Some realists (often called extreme realists) venture too close to solipsism and hold that both universals and particulars exist only in the mind. Yet extreme realists can only maintain this position by defining “particulars” differently than as having actual material existence.

There are, of course, variations of both. Some realists (often called extreme realists) venture too close to solipsism and hold that both universals and particulars exist only in the mind. Yet extreme realists can only maintain this position by defining “particulars” differently than as having actual material existence.

There are also less extreme nominalists (sometimes called “conceptualists” or “conceptual nominalists”) who will maintain that only particulars exist in matter and that universal do exist, but only in the mind. While this difference counts for some limited purposes of application, it amounts to the same thing as standard nominalism in practice. And, in fact, this difference again results more from conceptual nominalists defining “universals” differently from traditional nominalists and realists.

Interestingly, in the midst of modernity, we will find nominalism articulated and defended by conceptual nominalists more than by traditional nominalists. This is because it is often seen as a compromise of sorts to admit that we can share ideas of universals such as truth or justice, but that these ideas still lack reality in that they exist only in our heads. Thus, the conceptual nominalist will be happy to agree that the idea of justice, with diversity of definition, is still mentally shared by many people who, for example, want what they feel to be just outcomes in legal disputes. This kind of metaphysics is, in fact, the origin of both relativism and emotivism – the view that morality is only opinion, feeling, or attitude expressed by individuals, rather than standards that really and objectively exist outside subjective human minds or feelings.

To both the traditional and conceptual nominalists, there is no universal good or universal justice that really exists. A conceptual nominalist will therefore not agree that an unjust outcome, such as an impoverished elderly person having his pension fraudulently appropriated by an unscrupulous caregiver, is really and truly unjust. Instead, the conceptual nominalist will only agree that people think or feel of such a situation as unjust because of the idea they hold inside their heads. The actual deprivation of property that occurs in the real world is not, in and of itself, unjust to the conceptualist. In reality, person B simply possesses funds that were originally possessed by elderly person A, who was too weak to hold on to them. It is only in our heads that the transfer of property was unjust.

Conceptual nominalists try to frame the debate by sitting in the so-called middle position between the supposed extreme of realism on the one hand and the supposed extreme of nominalism on the other. But they do this only by excluding and ignoring the full range of viewpoints. Solipsism is truly an extreme that we can all agree is unhealthy. But if solipsism is an unhealthy extreme, then so is nominalism, because it simply turns solipsism on its head. The solipsist doesn’t like particular things intruding upon the ideas in his head, so he repudiates a large part of what makes reality meaningful. The nominalist doesn’t like universals intruding upon his use of his particular things, so he also repudiates a large part of what makes reality meaningful. Thus nominalists, not believing in objectively real universals, will further attempt to frame the “problem of universals” as a ridiculous one, in which some old outmoded thinkers insist on appealing to categorical abstractions when doing so is not really necessary. To nominalists, appealing to universals is merely a grandiose older way of speaking. Philosophy professor Brian Garrett is an example of someone who tries to characterize the debate in this way when he writes:

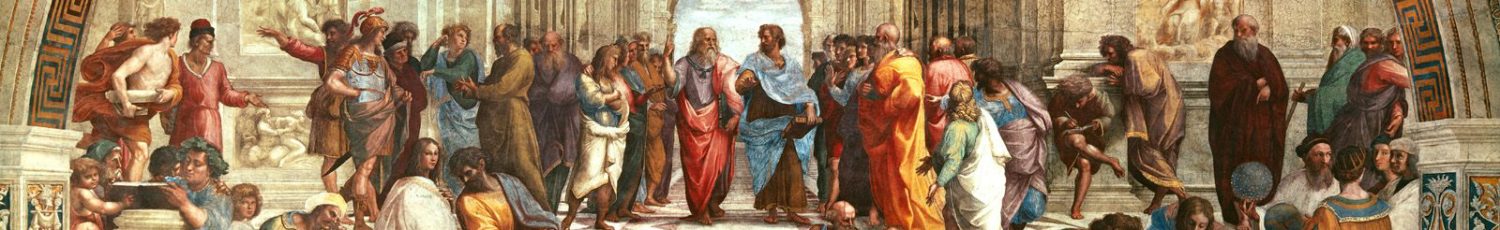

The problem of universals is one of the most venerable in metaphysics, dating back to Plato and Aristotle. At root, the problem concerns the nature of properties and relations. Are properties and relations universals, identical in their instances (as Plato and Aristotle thought), or can we explain, e.g., what it is for a sphere to be red, and hence what it is for two spheres to be the same colour, without appeal to universals? Philosophers who hold that we must appeal to universals in order to explain the nature of properties and relations are traditionally called ‘property realists’; those who deny this are traditionally called ‘nominalists’.

Like Garrett, most modern day nominalists will try to make metaphysics sound abstract, dry, and impractical. However, the problem of universals cannot be reduced to simply asking hypotheticals, such as “Is the color red a real property of a rose?” On the contrary, metaphysics is the very serious business of determining the nature of reality, meaning, ideas, and therefore our ability to live in the world. If it is true that I cannot live and act in the world without appealing to universals, then universals will be quite important. This is not to argue that dry abstract hypotheticals are necessary. It is that substances, properties, categories, limits, and standards exist in the real world and are what actually make both our knowledge and our action possible.

Furthermore, these questions have profound consequences for religious belief. Faith and reason can be united for a realist in ways that they can never be combined, or reconciled to each other, for a nominalist. This is why Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas are exemplary realists. They both worked out an elaborately coherent tradition of rational enquiry (with Aquinas building on Aristotle’s work) regarding what reality consists of and how we interact with it. This tradition has consequences for what ultimately matters and for what the difference is between order and disorder, coherence and incoherence, harmony and contradiction.

Furthermore, these questions have profound consequences for religious belief. Faith and reason can be united for a realist in ways that they can never be combined, or reconciled to each other, for a nominalist. This is why Aristotle and St. Thomas Aquinas are exemplary realists. They both worked out an elaborately coherent tradition of rational enquiry (with Aquinas building on Aristotle’s work) regarding what reality consists of and how we interact with it. This tradition has consequences for what ultimately matters and for what the difference is between order and disorder, coherence and incoherence, harmony and contradiction.

Aquinas is particularly famous for refuting the Averroists who argued, similar to the nominalists after them, that truth about the spiritual world was different, and contradictory to, truth about the physical world. Aquinas countered them by claiming that all truth is God’s truth. Therefore, no truth about the spiritual will ever contradict or diminish any truth about the physical. Likewise, any discoveries resulting from the investigation of matter will complement and inform any discoveries resulting from the investigation of mind. To the realist, mind and matter are not separate. The physical and spiritual affect, interact with, and permeate each other. Universals such as truth, love, justice, and mercy affect and shape the spheres of individuals and particulars. And, Aquinas argued, we can properly explore the order and relation between the two.

To the realist, truth is real. It is meaningful to hold that propositions, facts, conclusions, relations, or calculations are true. It is meaningful to say that a mathematical calculation, for example, regarding the weight of an object as a force against which the strength of a substance will hold, is a statement of mathematical truth that can directly correspond to the physical reality of a bridge not collapsing as objects are crossing it. If there are universal laws that help us understand the limits that make specific actions possible, then such universal laws are worth knowing and understanding. This will be equally true in the scientific work of a physicist, the historical work of a military tactician, or in the philosophical work of a scholar. Indeed, if there are universal laws that apply to the spiritual spheres, then anyone interested in his own spiritual health should be interested in the practical application of such universals. A psychologist who believes in the psychological good of laughter will be interested in such universals just as a doctor who believes in the physical good of exercise.

Yet, this metaphysical school of realism has been denied and rejected by nominalism. Famously, one of the most prominent advocates for nominalism was an English Franciscan theologian named William of Ockham (1287-1347). Ockham argued that the existence of any universal laws had to be denied because they would diminish the sovereignty of God. Consequently, Ockham taught that only particulars truly exist, and that universals are delusions contrary to a proper understanding of the will of God. As church historian Johann Heinrich Kurtz wrote of Ockham:

In accordance with his nominalistic principles he assumed the position in theology that our ideas derived from experience cannot reach to a knowledge of the supernatural; and thus he may be called a precursor of Kant (section 170, 10). The universalia are mere fictiones (section 99, 2), things that do not correspond to our notions; the world of ideas agrees not with that of phenomena, and so the unity of faith and knowledge, of theological and philosophical truth, asserted by realists, cannot be maintained (section 103, 2). Faith rests on the authority of Scripture and the decisions of the Church; criticism applied to the doctrines of the Church reduces them to a series of antinomies.

One interesting consequence of Ockham’s teaching is that nominalists tend to be literalist, legalistic, and fideist. If you deny universal law, then you must resort to the literal and specific meaning of only one particular thing or only one particular statement alone and without wider applicability. This often has arbitrary results. If you deny the correlation between reason and revelation, then the laws of revelation are less subject to being questioned. There are no universal standards by which to judge. You cannot, in fact, expect such laws to necessarily hold up to a reasoning or questioning process, because such laws are based upon God’s mere arbitrary Will rather than upon any knowledge or reason. If you reject the notion that anything coherent exists in the mind of God that corresponds to the material creation of God, then man’s knowledge must really depend upon a sort of blind faith that must simply be accepted without reasoning. This is because most reasoning and questioning, by its very nature, implies universal applicability.

While it is a subject that we could devote an entire book to exploring, the influence of Ockham’s nominalism upon mind/body dualism and upon the Enlightenment rationalism of René Descartes is both heavy and extensive. Epistemologically, both the rationalists and the empiricists that led the thinking of the Modern Age were also metaphysical nominalists. One nominalist conclusion led to the next which led to the next, and the Aristotelian realism that dominated Mediaeval philosophy was discarded by a metaphysics that denied all universals. Nominalism is what underlies the philosophy of Modernism. As philosopher and logician Charles Sanders Peirce wrote: “Descartes was a nominalist. Locke and all his following, Berkeley, Hartley, Hume and even Reid, were nominalists. Leibniz was an extreme nominalist … Kant was a nominalist … Hegel was a nominalist of realist yearnings. I might continue the list much further.” As it did for Ockham and his followers, this metaphysics has broad ranging theological consequences. Nominalism fundamentally denies intrinsic and underlying parts of reality.

While it is a subject that we could devote an entire book to exploring, the influence of Ockham’s nominalism upon mind/body dualism and upon the Enlightenment rationalism of René Descartes is both heavy and extensive. Epistemologically, both the rationalists and the empiricists that led the thinking of the Modern Age were also metaphysical nominalists. One nominalist conclusion led to the next which led to the next, and the Aristotelian realism that dominated Mediaeval philosophy was discarded by a metaphysics that denied all universals. Nominalism is what underlies the philosophy of Modernism. As philosopher and logician Charles Sanders Peirce wrote: “Descartes was a nominalist. Locke and all his following, Berkeley, Hartley, Hume and even Reid, were nominalists. Leibniz was an extreme nominalist … Kant was a nominalist … Hegel was a nominalist of realist yearnings. I might continue the list much further.” As it did for Ockham and his followers, this metaphysics has broad ranging theological consequences. Nominalism fundamentally denies intrinsic and underlying parts of reality.

Whether they believe in a divine Creator or not, both believers and nonbelievers admit that there is an order that underlies our existence, whether that order is mathematical, evolutionary, a matter of biology, or a matter of physics. Realism is fundamentally interested in learning about the intrinsic and underlying parts of reality. Particular things have relations with other particular things. These relations are sometimes causal relations, and they follow laws. Both particular things and the relations of particular things share different qualities that work over time and space. Ecology and sociology explore some of these relations in reality as they develop over time. That some, if not all, of this order is of universal application has been demonstrated in many different fields and sciences. There are different levels of interaction, permeation, and spheres of relation and order. This goes to show the infinite levels of complexity to existence. Realism accepts and explores this complexity. Nominalism denies that these observed interactions and relations have any correspondence to reality. Taking Ockham and Descartes at their word, nominalists end up sacrificing and diminishing what otherwise allows for a broader, richer, and more comprehensive view of reality. This affects the very way that a nominalist thinks. For, as A.G. Sertillanges writes, a realist thinks in terms of correspondence between mind and particular things:

The order of the mind must correspond to the order of things; and since the mind does not really learn except by seeking out the relation of cause and effect, the order of the mind must correspond to the order of causes. If then there is a first Being and a first Cause, it is there that ultimate knowledge and light are attained. First as a philosopher, by means of reason, then as a theologian, utilizing the light from on high, the man of truth must center his research in what is at once the point of departure, the rule, the supreme and ultimate goal; in what is all to all things, and to all men.

Rather than arguing about whether a pursuer of truth should do this, we have been focusing here upon what happens when the pursuer of truth does not do this. This is to show that how you answer the question of whether there is an intrinsic and underlying ground to reality will determine how you interpret meaning itself. One of the reasons I am now a Catholic is because, in general, Evangelicalism and Protestantism do not pay any attention to how nominalism informs their theology. In fact, rarely will a Protestant teacher even admit (usually because he has never thought about it) that his school of thought in metaphysics is a preunderstanding that fundamentally determines his interpretation of Scripture. One notable exception to the rule is the Reformed theologian Hans Boersma.

The Necessity of Metaphysics for Biblical Interpretation

Hans Boersma, in his 2017 book, Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church, points out how modern Christians “often treat biblical interpretation as a relatively value-free endeavor, as something we’re equipped to do once we’ve acquired both the proper tools (biblical languages, an understanding of how grammar and syntax work, the ability to navigate concordances and computer programs, etc.) and a solid understanding of the right method (establishing the original text and translating it, determining authorship and original audience, studying historical and cultural context, figuring out the literary genre of the passage, and looking for themes and applicability).” But it is important to understand that this is a recent view and it is not how ancient Christian believers, teachers, theologians, and commentators interpreted Scripture through the first fifteen hundred years of church history.

Hans Boersma, in his 2017 book, Scripture as Real Presence: Sacramental Exegesis in the Early Church, points out how modern Christians “often treat biblical interpretation as a relatively value-free endeavor, as something we’re equipped to do once we’ve acquired both the proper tools (biblical languages, an understanding of how grammar and syntax work, the ability to navigate concordances and computer programs, etc.) and a solid understanding of the right method (establishing the original text and translating it, determining authorship and original audience, studying historical and cultural context, figuring out the literary genre of the passage, and looking for themes and applicability).” But it is important to understand that this is a recent view and it is not how ancient Christian believers, teachers, theologians, and commentators interpreted Scripture through the first fifteen hundred years of church history.

The modern view focuses entirely upon method. You have to get the method right, and you can then get the “meaning extraction” right. “In other words,” as Boersma demonstrates, “the assumption is that the way to read the Bible is by following certain exegetical rules, which in turn are not affected by the way we think of how God and the world relate to each other. Metaphysics, on this assumption, doesn’t affect interpretation.”

So what do we do with this assumption? If metaphysics does affect one’s interpretation of Scripture, then we better have a coherent and properly working metaphysics. The problem with this conclusion is that most of us have no idea what our metaphysics is, let alone do we have any notion of the different competing traditions and schools of metaphysics. So we end up automatically and unintentionally subscribing to one school of metaphysics without being aware of it. Sometimes, we even end up thinking and interpreting incoherently as if we agree with one metaphysical proposition one moment and then a completely contradictory metaphysical doctrine the next moment, jumbling together misfitting fragments of what were consistent chains of reasoning from conflicting traditions in the past, taken out of context, and used without understanding as to what they mean or what they were for. Boersma argues that, for the ancient Christian understanding:

[M]etaphysics does affect one’s interpretation, and it seems to me that [this fact] gives us much food for thought, whereas modern attempts to separate biblical interpretation from metaphysics appear to me misguided. Historically, it is clear that changes in metaphysics and hermeneutics have gone hand in hand. The separation between nature and the supernatural – or, we might say, between visible and invisible things – first philosophically advocated by William of Ockham (ca. 1287-ca. 1347), led to attempts to isolate biblical interpretation from metaphysics … Ockham’s philosophy decisively abandons the earlier Christian Platonist assumption of eternal patterns or ‘forms’ expressing themselves within the objects of the empirical world around us. Ockham’s philosophical position, commonly known as nominalism, was to have profound consequences for biblical interpretation.

So this is where the rubber meets the road in determining how you interpret a text of Scripture. If Scripture was written with a particular school of metaphysics assumed by its authors (a school of metaphysics that was shared by Plato and Aristotle along with Moses and the apostles), then the interpreter will only be able to properly interpret the text by taking this into account. Boersma continues his argument by explaining that philosopher Thomas Hobbes was greatly influential in making nominalism the Rationalist school of metaphysics in the West. This, in turn, affected modern assumptions about the nature of words, of meaning, and of reality itself. Boersma explains:

Hobbes’ book Leviathan (1641) suggests that the underlying cause of the wars of religion was a slavish following of Aristotle over Scripture. Aristotle’s claim that ‘being’ and ‘essence” have real existence lies at the root of the problem, according to Hobbes. He counters Aristotelian philosophy by insisting that universal notions are just words and that we should treat them accordingly. Though we employ such notions – ‘man,’ ‘horse,’ and ‘tree’ – Hobbes urges his readers to keep in mind that these are merely names ‘of divers particular things; in respect of all which together, it is called an Universall; there being nothing in the world Universall but Names; for the things named, are every one of them Individuall and Singular.’ Put differently, Hobbes’s metaphysics follows that of Ockham: both reject the notion that visible things have real relations to invisible things. [bold added]

If you believe that words are just names that are arbitrarily assigned to things, that things do not mean or signify anything greater than their own particular existences, and that meaning is only contained within our minds and languages and not within physical reality itself, then you will not be able to help interpreting Scripture as a nominalist interprets the language of a text. However, if you believe that things do mean or symbolize something more than their own individual particulars, that meaning is both inside and outside our own minds and languages, that physical reality is endowed with its own meanings, then you will interpret Scripture quite differently. So, by process of reasoning, the next follow-up question is obvious:

If you believe that words are just names that are arbitrarily assigned to things, that things do not mean or signify anything greater than their own particular existences, and that meaning is only contained within our minds and languages and not within physical reality itself, then you will not be able to help interpreting Scripture as a nominalist interprets the language of a text. However, if you believe that things do mean or symbolize something more than their own individual particulars, that meaning is both inside and outside our own minds and languages, that physical reality is endowed with its own meanings, then you will interpret Scripture quite differently. So, by process of reasoning, the next follow-up question is obvious:

What would interpreting Scripture look like with an ancient or a Mediaeval metaphysics?

The Metaphysical Interpretation of Scripture Across Church History

It is difficult to describe the incredible depth of interpreting Scripture without using selections from the works of the greatest theologians who have shown how it’s done. As someone who had never read the theologians of the first fifteen centuries of the history of the Church until recently, I can only express that the rigor, the richness, the coherence, the beauty, and the wisdom of their interpretive work constantly continues to surprise me. I had never, after only being given a diet of modern theological teaching, heard or experienced anything like it. If you have never taken the time to immerse yourself in it, you will never be able to guess what it is like to spend hours with a mind such as that of St. Athanasius, St. Gregory of Nazianzus, St. John Chrysostom, or St. Anselm. The experience is unfamiliar, unpredictable, startling, and eye opening.

There is an exciting moment in the Gospels when Jesus, at the beginning of his ministry, makes his entrance into the synagogue in Nazareth and stands up to read. “And the book of Isaias the prophet was delivered unto him. And as he unfolded the book, he found the place where it was written: The Spirit of the Lord is upon me. Wherefore he hath anointed me to preach the gospel to the poor, he hath sent me to heal the contrite of heart, To preach deliverance to the captives, and sight to the blind, to set at liberty them that are bruised, to preach the acceptable year of the Lord, and the day of reward. And when he had folded the book, he restored it to the minister, and sat down. And the eyes of all in the synagogue were fixed on him. And he began to say to them: This day is fulfilled this scripture in your ears.” (Luke 4:17-21).

Taking this dramatic moment into account, along with the fact that one can imagine how the power of his reading caused the awed silence where“the eyes of all in the synagogue fixed on him” before he utters a single word to interpret the passage, there is a sense in which Christ does not just interpret this passage in its literal historical sense. When he says, “now, this day, this Scripture is fulfilled because I am here,” this means that these words are no longer just the prophet Isaiah speaking. Instead, the prophet Isaiah himself is writing as a Christ figure. The literal physical existence of the prophet Isaiah, writing in his own historical context, meant and still means Christ.

If you look at the beginning of Church history, you will see that for the first couple centuries, the leaders and teachers of the Church expended most of their time in Scripture interpretation with the Old Testament. Even the risen Christ, during his walk with the two men on the road to Emmaus, began with “Moses and all the prophets” and “expounded to them in all the scriptures, the things that were concerning him.” (Luke 24:27). The apostles followed Christ’s example, and their practice of hermeneutics was to show how Old Testament Scripture meant and referred to Christ. (See Acts 2:14-40; 7:2-53; 8:26-39; 13:14-52.) Eventually, as the heresy of Gnosticism began to spread, theologians such as Theophilus of Antioch and Irenaeus of Lyons began to quote and interpret New Testament Scripture more frequently in order to counter Gnostic misinterpretations.

Clement of Alexandria (160-215) began the work of using Greek philosophy, including ideas such as the Logos, to help interpret Scripture in its full context. Origen (185-254) appears to be the first theologian who made the distinction between the literal sense and the spiritual sense of a Scriptural text, and Origen also helped form the tradition of exegetical (expository) preaching that focused on digging into the deeper meaning of an individual text. Both Clement and Origen taught that much of Scripture could be taught allegorically, in which different individuals and different objects symbolized parts of our present spiritual life – and this development in interpretation was called the Alexandrian school. Origen’s interpretative practices later influenced the works of Ambrose of Milan, Hilary of Poitiers, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa, all of whom helped fuse philosophical principles into precise and important doctrinal distinctions in order to protect the teaching of the Trinity, and the divine and human natures of Christ.

Clement of Alexandria (160-215) began the work of using Greek philosophy, including ideas such as the Logos, to help interpret Scripture in its full context. Origen (185-254) appears to be the first theologian who made the distinction between the literal sense and the spiritual sense of a Scriptural text, and Origen also helped form the tradition of exegetical (expository) preaching that focused on digging into the deeper meaning of an individual text. Both Clement and Origen taught that much of Scripture could be taught allegorically, in which different individuals and different objects symbolized parts of our present spiritual life – and this development in interpretation was called the Alexandrian school. Origen’s interpretative practices later influenced the works of Ambrose of Milan, Hilary of Poitiers, Gregory of Nazianzus, and Gregory of Nyssa, all of whom helped fuse philosophical principles into precise and important doctrinal distinctions in order to protect the teaching of the Trinity, and the divine and human natures of Christ.

With different emphasis, another development in Scripture interpretation arose from Athanasius (296-373) and Theodore of Mopsuestia (350-428), who tempered and corrected some of the more allegorical interpretations coming out of Alexandria. They emphasized the importance of continuing to interpret Scripture literally and historically. Athanasius checked the Arians’ proclivity to attempt to primarily rely upon only allegorical interpretation. Theodore’s critical hermeneutical work, taking scientific and philological analysis into consideration, could rival any modern scholarship attempting the same. The resulting Antiochian (or Antiochene) School complemented the Alexandrian School, and it is by putting both schools of interpretation into a harmonious whole that the Church has affirmed and taught the multiple senses of Scripture.

Meanwhile, some of the church’s greatest theologians, such as St. Jerome (347-420) and St. Augustine (354-430), developed Biblical hermeneutics in other ways. While Jerome did not write any work formally focusing on hermeneutics, he did occasionally give some commentary on interpreting Scripture as he wrote and discussed Scriptural translations and their comparison to the original Greek and Hebrew. In Jerome’s writing on Biblical themes, he often distinguished between two senses of Scripture: combining the literal and historical (simpliciter) sense and contrasting it with the spiritual (mystica intellegentia) sense. Finally, Jerome eventually added that Scripture ought to also be interpreted in the moral sense, and thus distinguished Scriptural meaning into three senses: “We can describe the three ways by which the instructions and regulations of Scripture are set forth in our hearts. First there is the literal and historical sense. Second, there is the moral sense. And, finally, it may be taken in the spiritual sense.”

Reading Augustine on the subject of Scripture interpretation is fascinating, not only because he applies the rigor of classical Ciceronian rhetoric to his explanation of hermeneutical rules, but also because he maintains an independence both from the Antiochian and Alexandrian schools. Most elaborated in his work entitled De doctrina christiana, Augustine hints at his metaphysics when he devotes an extensive discussion of the difference between figures and things. Augustine writes a whole discourse upon how all figures are not things but how all things are figures. This understanding ruled his method of interpretation, and Augustine elaborated it further with examples on the seven exegetical rules of Tyconius. Perhaps one of the most important facts about Augustine’s interpretation of Scripture is that he deeply felt the objection to interpreting the Scripture only literally, which some of his contemporary North African Christians insisted upon. It was only by hearing the preaching of St. Ambrose, who interpreted Scripture more than literally, that the Manichaean Augustine, before he converted, began to find his way toward what it could mean to rightly interpret and teach Scripture. Augustine wrote in his Confessions of what happened after he listened to St. Ambrose:

First of all, it struck me that it was, after all, possible to vindicate his arguments. I began to believe that the Catholic faith, which I had thought impossible to defend against the objections of the Manichees, might fairly be maintained, especially since I had heard one passage after another in the Old Testament figuratively explained. These passages had been death to me when I took them literally, but once I heard them explained in their spiritual meaning I began to blame myself for my despair, at least in so far as it had led me to suppose that it was quite impossible to counter people who hated and derided the law and the prophets.

Augustine’s writing is richer than you will ever understand unless you have not invested the time into reading his work. He ended up supporting allegorical interpretation of Scripture in some unique and creative ways. But it would take other theologians to correct some of Augustine’s tendency to sometimes make arguments for doctrine from his allegorical interpretations. [“[F]or all the senses are founded on one – the literal – from which alone can any argument be drawn, and not from those intended in allegory, as Augustine says.” See Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Tenth Article of Question One from Part One.] The way in which Augustine finds depth in Scripture can be quite beautiful, and he is a rigorous thinker, but outside De doctrina christiana, he did not engage in an extended discourse on hermeneutics.

Augustine’s writing is richer than you will ever understand unless you have not invested the time into reading his work. He ended up supporting allegorical interpretation of Scripture in some unique and creative ways. But it would take other theologians to correct some of Augustine’s tendency to sometimes make arguments for doctrine from his allegorical interpretations. [“[F]or all the senses are founded on one – the literal – from which alone can any argument be drawn, and not from those intended in allegory, as Augustine says.” See Aquinas, Summa Theologica, Tenth Article of Question One from Part One.] The way in which Augustine finds depth in Scripture can be quite beautiful, and he is a rigorous thinker, but outside De doctrina christiana, he did not engage in an extended discourse on hermeneutics.

There is, of course, a great deal more to how the history of hermeneutics developed as the Church grew over its first three centuries, and Donald K. McKim, in his Historical Handbook of Major Biblical Interpreters, does a tremendous job at introducing and summarizing the contributions of some of the Church’s greatest theologians to Biblical hermeneutics. For the sake of space and for the purposes of exploring how metaphysics shapes Scripture interpretation, we will focus upon four notable contributions to the Church’s established hermeneutical tradition; namely, John Cassian (360-435); the School of Saint Victor (1115-1173); Thomas Aquinas (1225-1274); and Nicholas of Lyra (1270-1349).

John Cassian on Scripture Interpretation

St. John Cassian (360-435), a contemporary of St. Augustine, is a sometimes neglected great theologian of the early fifth century of the Church. He is important to mention here, because he is one of the earliest Christian theologians who wrote extensively about how to interpret Scripture in different senses and with different levels of meaning. What is compelling about Cassian is not only that his metaphysics clearly shapes his Scripture interpretation, but he actually affirms the idea that one’s preunderstanding shapes how one interprets. In the Conferences of the Desert Fathers, which Cassian wrote around the year 420, Cassian teaches that “as the renewal of our soul grows by means of study, Scripture also will begin to put on a new face, and the beauty of the holier meanings will somehow grow with our growth.” The more one studies, the deeper the sense of meaning one will be able to see. Cassian’s teaching on the senses of Scripture, which built both upon the work of St. Jerome and upon the Alexandrian and Antiochian schools, has been adopted by the Catholic Church. Cassian was a check that corrected some of Augustine’s teachings on predestination and original sin, and Cassian can be considered one of the most well-balanced and dependable early authorities on how to properly interpret Scripture.

Cassian was firmly convinced that, as we practice devotions, study, and learn more, we will be able to see more, because of how our deeper study shapes our comprehension of what is taught. Thus, the Scriptural meaning’s “form is adapted to the capacity of man’s understanding, and will appear earthly to carnal people, and divine to spiritual ones, so that those to whom it formerly appeared to be involved in thick clouds, cannot apprehend its subtleties nor endure its light.” (Conference 14, Chapter 11). But those who practice the work of regular study will increase their capacity to apprehend the Holy Spirit’s meaning in the text. If the form of meaning is adapted to the capacity of one’s understanding, then the degree, level, or depth of any meaning one receives from interpreting Scripture will depend upon the understanding one brings to the text.

Cassian was firmly convinced that, as we practice devotions, study, and learn more, we will be able to see more, because of how our deeper study shapes our comprehension of what is taught. Thus, the Scriptural meaning’s “form is adapted to the capacity of man’s understanding, and will appear earthly to carnal people, and divine to spiritual ones, so that those to whom it formerly appeared to be involved in thick clouds, cannot apprehend its subtleties nor endure its light.” (Conference 14, Chapter 11). But those who practice the work of regular study will increase their capacity to apprehend the Holy Spirit’s meaning in the text. If the form of meaning is adapted to the capacity of one’s understanding, then the degree, level, or depth of any meaning one receives from interpreting Scripture will depend upon the understanding one brings to the text.

Cassian, moreover, does not treat Scripture interpretation as it is practiced today in the modern sense. As Christopher J. Kelly writes, in his book Cassian’s Conferences: Scriptural Interpretation and the Monastic Ideal, Cassian interprets Scripture in order to explain the devotional life and he does so by requiring a level of interaction between the text and the reader that we rarely imagine or hear taught today. “The result is” Scripture interpretation “that immerses the reader in the world of the biblical text and demands that one emerge again a changed person. Indeed, Cassian would have his reader become a living embodiment of the sacred pages.” We sometimes can forget how incarnational in its thinking the early Church was. It’s certainly one thing if you read a text in order to understand it, and come away from that with practical knowledge that you can apply differently to your life. It’s certainly another thing altogether if you read a text in order to become a living embodiment of the text. This is metaphysics meeting hermeneutics. There is a difference of thinking here about the nature of reality itself, and there is a mixing of universals and particulars in ways that we do not really allow for in our current age. Kelly tries to explain Cassian’s approach to Scripture in more detail when he writes:

For Cassian, engagement with the scriptures through reading, meditation, and, especially, imitation … had very real effects upon the monk’s body, mind, and soul. His Conferences is an exercise in patristic exegesis that affirms the possibility of the monk dwelling in the scriptures, and the scriptures in him, in the sense that the monk’s life becomes the hermeneutical medium for understanding the text … Building on the pedagogical tradition of mimesis, or “imitation,” common in the philosophical and monastic circles of the East, Cassian’s Conferences employs a subtle use of biblical archetypes to express his vision of the monastic ideal. The result is an interpretive methodology that is primarily tropological and designed to complement the transformative effect of scriptural reading that Cassian and his contemporaries took for granted. [bold added]

The term tropological (having a moral significance) is an important one, because the Church has traditionally organized the different meanings of the Scriptural text into four different categories. Cassian gives us one of the earliest detailed descriptions of these four categories, which include (1) the literal (and historical), (2) the tropological, (3) the allegorical, and (4) the anagogical. In Conference 14, Chapter 8, Cassian writes that the meanings of Scripture can be first “divided into two parts, i.e., the historical interpretation and the spiritual sense.” Cassian then continues:

Whence also Solomon when he had summed up the manifold grace of the Church, added: “for all who are with her are clothed with double garments.” But of spiritual knowledge there are three kinds, tropological, allegorical, anagogical, of which we read as follows in Proverbs: “But do you describe these things to yourself in three ways according to the largeness of your heart.” And so the history embraces the knowledge of things past and visible … But to the allegory belongs what follows, for what actually happened is said to have prefigured the form of some mystery … But the anagogical sense rises from spiritual mysteries even to still more sublime and sacred secrets of heaven … The tropological sense is the moral explanation which has to do with improvement of life and practical teaching … Of these four kinds of interpretation the blessed Apostle speaks as follows: “But now, brethren, if I come to you speaking with tongues what shall I profit you unless I speak to you either by revelation or by knowledge or by prophecy or by doctrine?” 1 Corinthians 14:6. For “revelation” belongs to allegory whereby what is concealed under the historical narrative is revealed in its spiritual sense and interpretation … But the “knowledge,” which is in the same way mentioned by the Apostle, is tropological, as by it we can by a careful study see of all things that have to do with practical discernment whether they are useful and good … So “prophecy” which the Apostle puts in the third place, alludes to the anagogical sense by which the words are applied to things future and invisible … But “doctrine” unfolds the simple course of historical exposition, under which is contained no more secret sense, but what is declared by the very words …

Note that all these multiple senses do not include contradictory meanings. Instead, this involves levels and degrees of meaning that are neither contradictory nor mutually exclusive. We will follow the continued affirmations of the different senses of the meaning of Scripture as we continue, but it is worth noting that Cassian takes the time to carefully lay out different texts as examples to illustrate his teaching. While we do not have the space to explore them here, it is worth reading the Conferences in their entirety to work through all his examples. Also important is that while Cassian occasionally speaks of what is sometimes called a “secret” or “hidden” meaning in his examples and illustrations, he does not suggest by this that there is any special secret knowledge that is only for the special elite few. The purpose of Cassian’s teaching here is to show any teacher of Scripture how to properly study and interpret in order to teach anyone and everyone. These are meanings that are for all believers and for all hearers, even if particular work is required in order to reach them.

Note that all these multiple senses do not include contradictory meanings. Instead, this involves levels and degrees of meaning that are neither contradictory nor mutually exclusive. We will follow the continued affirmations of the different senses of the meaning of Scripture as we continue, but it is worth noting that Cassian takes the time to carefully lay out different texts as examples to illustrate his teaching. While we do not have the space to explore them here, it is worth reading the Conferences in their entirety to work through all his examples. Also important is that while Cassian occasionally speaks of what is sometimes called a “secret” or “hidden” meaning in his examples and illustrations, he does not suggest by this that there is any special secret knowledge that is only for the special elite few. The purpose of Cassian’s teaching here is to show any teacher of Scripture how to properly study and interpret in order to teach anyone and everyone. These are meanings that are for all believers and for all hearers, even if particular work is required in order to reach them.

Depth and multiple senses of a text does not mean that the text is only for privileged elites. The entire point is that Scripture has riches and nourishment for all. The literal and historical, more easily understood without instruction by the common person on the street, points toward and leads to deeper degrees of meaning – the spiritual, the moral, and the realm beyond death. By revealing deeper meanings that are secret until revealed by the hard work of prayer, devotion, and study, Cassian does not mean to be revealing some exclusive gnosis that is meant to be hidden to the common people. Simply because some truths are only uncovered by hard work and study does not mean that those truths are only meant for a favored few. In Conference 8, Chapter 3, Cassian writes:

And so holy Scripture is fitly compared to a rich and fertile field, which, while bearing and producing much which is good for man’s food without being cooked by fire, produces some things which are found to be unsuitable for man’s use or even harmful unless they have lost all the roughness of their raw condition by being tempered and softened down by the heat of fire … And we can clearly see that the same system holds good in that most fruitful garden of the Scriptures of the Spirit, in which some things shine forth clear and bright in their literal sense, in such a way that while the have no need of any higher interpretation, they furnish abundant food and nourishment in the simple sound of the words, to the hearers: as in this passage: Hear, O Israel, the Lord your God is one Lord; and: You shall love the Lord your God with all your heart, and with all your soul, and with all your strength. Deuteronomy 6:4-5.

There is great wisdom, beauty, depth, and edification to be found in those texts of Scripture that are simple, clear, and literal. Simplicity and clarity are strengths that ought to be valued for what they can bring us. Some texts have only literal or historical meanings. Some texts have only metaphorical or poetic meanings. “But some” texts, Cassian teaches, “are capable of being taken suitable and properly in both ways, i.e., the historical and allegorical, so that either explanation furnishes a healing draught to the soul.” All of this is valuable, and the more that we study Scripture and the more that we explore what it has to offer us, the more of it we will be able to see.

Today, the theological writings of Ancient and Mediaeval times are criticized for taking texts too allegorically or too metaphorically. Some allegories were certainly taken too far by ancient interpreters. And allegorical interpretation is surely easy to abuse. But it is also possible to take literal interpretation too far. Cassian, in 420 A.D., criticizes being overly literal, and cites Matthew 10:38 (“whosoever takes not up his cross and follows after Me is not worthy of Me;”) as an example of “a passage which some most earnest monks, having indeed a zeal for God, but not according to knowledge understood literally, and so made themselves wooden crosses, and carried them about constantly on their shoulders, and so were the cause not of edification but of ridicule on the part of all who saw them.” So it is critical for us, when we consider abuses in hermeneutics, to understand that both literal and metaphorical interpretation can be taken too far. There are extremes on both sides that can be cause for misunderstanding.

Note that Cassian states that these literalists had “indeed a zeal for God.” Energy and zealousness were, however, not enough. Being passionate and earnest in interpreting Scripture does not guarantee accurate interpretation. Rather, it is by “careful study,” hard work, and discernment that right interpretation is found. Then, the meaning revealed “is adapted to the capacity of” the interpreter’s understanding. Thus, it is distorted for a reader of Scripture to only be a “literalist” just as it would be distorted to only be a “allegoricalist” or to only be a “moralist.” Scripture is too rich for that, and anyone who tries to limit what is in the text can only attempt to impose their finiteness upon what is certainly not finite.

Note that Cassian states that these literalists had “indeed a zeal for God.” Energy and zealousness were, however, not enough. Being passionate and earnest in interpreting Scripture does not guarantee accurate interpretation. Rather, it is by “careful study,” hard work, and discernment that right interpretation is found. Then, the meaning revealed “is adapted to the capacity of” the interpreter’s understanding. Thus, it is distorted for a reader of Scripture to only be a “literalist” just as it would be distorted to only be a “allegoricalist” or to only be a “moralist.” Scripture is too rich for that, and anyone who tries to limit what is in the text can only attempt to impose their finiteness upon what is certainly not finite.

This is metaphysics practically applied to hermeneutics. If Cassian is right, then Scripture has much more than only a literal meaning. It also has a spiritual meaning, which can be moral, allegorical, or prophetic. This is not the same thing as what a literalist will mean by literary genres. While a six-year-old literalist in the first grade may have some trouble grasping the fact that one does not interpret poetry literally as one does not interpret history metaphorically, most adult literalists will admit that one interprets poetry, proverbs, or parables literally by recognizing what poetry, proverbs, and parables are. The literal meaning of a poem in Scripture is seen by interpreting that poem as a poem. (Theodore of Mopsuestia is known for arguing that Song of Songs is only a poem.) But that is not what Cassian means here.

Cassian teaches that even a historical text can have other symbolic meanings. This depends upon the metaphysics assumed by Scripture. Because of the nature of reality that Scripture describes, literal historical particular individuals and objects can, according to Cassian, act out, personify, and symbolize greater allegorical or moral meanings. David’s harp is a literal physical musical instrument, but it means more than a musical instrument. Joseph’s literal actual human sufferings on earth points to greater and bigger ends. The widow’s mite is a coin, but means more than a coin. The pearl of great price is a literal pearl, but its purchase means more than a mere utilitarian calculus. The manna from heaven is literal bread from heaven, but also means much more than bread from heaven. The number forty is a mere number that can be used to count days or years, but it also means something more than its number. The queen mother of the king in the Kingdom of David is a literal woman who is the monarch of a royal house, but her particular existence means and points to something greater. The burning bush is a literal plant with leaves not being consumed by fire that really burned, but it also signifies something more. The story of the history of the ark of the covenant is really a historical narrative of God’s presence among the nation of Israel, but the historical narrative means more than only history.

Angelomus of Luxeuil, a Colombanian monk from Luxeuil, Franche-Comté, who lived in the ninth century, in his prologue to his commentary on Samuel and Kings, affirmed Cassian’s insight into Scripture interpretation when he wrote:

Although some people, who do not know how to understand [Scripture] spiritually, or are dedicated only to human wisdom, say that nothing else can be understood but the surface of the history, and the struggles of kings and the vicissitudes of many; yet in this volume many things appear to contain the mysteries of Christ and the Church in several ways.

It is important to emphasize that multiple senses of meaning does not allow for the reduction of Scripture into purely symbolic, mythological abstractions which contain airy stories of figurative symbols which never actually had literal historical physical existence. Interpreting historical narrative as only symbolic and not really historical is both Gnostic and nominalist, and it was not the practice of the theologians of the early Church. The realist metaphysics exemplified by Cassian demands that the literal, historical, and physical is real in Scripture. These are not just myths or abstractions that we are dealing with. These are myths that were incarnated physically and then entered history – figurative myths that ended up being really and literally true.

In order to understand this, Cassian gives the Church a greater sense for the depth of multiple meanings which is contained by Scripture, but he does not directly apply the problem of universals to the interpretation of Scripture. From the view of metaphysics, a nominalist has less trouble with a text possessing multiple meanings than he would with such meanings having universal scope or application. Cassian delivers a blow to nominalism by teaching that meaning was really contained within particular persons and things. But there was still more work to be done. One of the first theologians to explicitly apply his view of universals existing in reality to interpreting Scripture was Hugh of Saint Victor.

The School of Saint Victor on Scripture Interpretation

The School of Saint Victor (1115-1173) was a monastic school located in the abbey of St. Victor in Paris. It was founded around 1115 by William of Champeaux (1070-1121), and the first prominent head of the school was Hugh of Saint Victor. Eventually, two of Hugh’s students, Achard of Saint Victor and Richard of Saint Victor also rose in leadership, and other theologians, including Andrew, Godfrey, and Walter, all wrote works or commentaries which have lasted over time. Known as the “Victorines,” all members of the school were Augustinians, and they all wrote works that discussed the rules of hermeneutics for the interpretation of Scripture. Another aspect of the Victorines that contributed to the breadth of their thought was the diversity of nationality of their members, characteristic of Mediaeval universities of that time. William and Godfrey were French. Hugh was Saxon. Achard and Andrew were English. Richard was Scottish. We will focus here on the two most iconic members of the group, Hugh and Richard.

The School of Saint Victor (1115-1173) was a monastic school located in the abbey of St. Victor in Paris. It was founded around 1115 by William of Champeaux (1070-1121), and the first prominent head of the school was Hugh of Saint Victor. Eventually, two of Hugh’s students, Achard of Saint Victor and Richard of Saint Victor also rose in leadership, and other theologians, including Andrew, Godfrey, and Walter, all wrote works or commentaries which have lasted over time. Known as the “Victorines,” all members of the school were Augustinians, and they all wrote works that discussed the rules of hermeneutics for the interpretation of Scripture. Another aspect of the Victorines that contributed to the breadth of their thought was the diversity of nationality of their members, characteristic of Mediaeval universities of that time. William and Godfrey were French. Hugh was Saxon. Achard and Andrew were English. Richard was Scottish. We will focus here on the two most iconic members of the group, Hugh and Richard.

After the first thousand years of the church, it was growing more and more common to quote from the church’s best theologians in order to teach and preach. While this resulted in a great deal of use of the works of the Church fathers, it also began to be practiced uncritically and sometimes incoherently. Origen or Augustine were cited in support of a particular teaching or position on doctrine, not because of the substance of what they had to say, but simply because of who they were. This began to be used in a way that was often lazy and poorly thought out (imagine a preacher compiling a sermon now from BrainyQuote.com instead of actually reading and thinking through the text and subject matter). As often happens with time and inertia, there was a need for renewal for a more critical use of the first millennia of Bible commentary. This is where Hugh of Saint Victor stepped up.

Hugh of Saint Victor (1096-1141) wrote one of the Church’s masterworks on the interpretation of Scripture. It was carefully crafted from his teaching and lectures from the 1120s through the 1140s, and it was entitled the Didascalicon, or, On the Study of Reading. In this work, Hugh argued that all of general revelation was necessary, proper, and helpful in order to properly interpret the special revelation of Scripture. This meant that the entirety of the Liberal Arts, the trivium and quadrivium, were all vital to a properly informed, literate, scholarly, and coherent hermeneutics. As Frans van Liere writes:

For Hugh (following Augustine), God speaks to people in two ways: through his Word (Scripture in its overt meaning) and, on a secondary level, through the created world (through things, facts, and deeds). Or, in the words of Alan of Lille (d. 1203), the whole world could be seen as a book, written by God’s hand. The Bible was not only the word of God but also the record of God’s deeds in history, and it therefore had a double meaning: the words had an overt meaning, but they also signified the higher reality of salvation history, which had its culmination in salvation through Jesus Christ … This way of reading the Bible was more than just free allegorization; one needed a good basic comprehension of historical facts through literal exegesis before one could apprehend the spiritual dimension of Scripture. Allegorization could never contradict the historical sense of salvation history narrated in the Bible. Hugh saw the literal, historical meaning of the text as the foundation on which one could erect the building of faith. Allegory, which established Christian doctrine, formed its walls, and moral behavior was its exterior covering.

Hugh, by organizing and ordering how to read and consider the meanings of a text, thus introduced some much needed discipline to the use and teaching of the four senses of Scripture. Some interpreters would insist upon finding all four senses in one passage of Scripture, no matter how strained or ludicrous the result. Hugh cautioned that all meanings were not required: “To be sure, all things in the divine utterance must not be wrenched to an interpretation such that each of them is held to contain history, allegory, and tropology all at once.” The method of interpretation should not, Hugh argued, be done rotely or mechanically. There was room for diversity in the number of meanings for different texts because, “in the divine utterances are placed certain things which are intended to be understood spiritually only, certain things that emphasize the importance of moral conduct, and certain things said according to the simple sense of history.” The practice of twisting interpretations out of the text by following a copied formula was, Hugh wrote, a mistake. Any Protestant literalist who believes Mediaeval hermeneutics resulted in bizarre and fantastical allegories would find much admire in Hugh of Saint Victor’s more measured and temperate words of caution in the Didascalicon. “And yet,” Hugh wrote, affirming the multiple meanings in Scripture, “there are some things which can suitably be expounded not only historically but allegorically and tropologically as well.”

Beyond his order and his temperance, Hugh did more than apply critical rules of reason to sober discernment of the senses of Scripture. We began this essay by looking at the major schools of thought in metaphysics. Nominalists affirm the existence of particulars and deny the existence of universals. Realists affirm the existence of both universals and particulars. These differences affect one’s hermeneutics. Hugh of Saint Victor was a realist, and he logically discusses the application of the realist school of metaphysics to the interpretation of a Scriptural text:

The method of expounding a text consists in analysis. Every analysis begins from things which are finite, or defined, and proceeds in the direction of things which are infinite, or undefined. Now every finite or defined matter is better known and able to be grasped by our knowledge; teaching, moreover, begins with those things which are better known and, by acquainting us with these, works its way to matters which lie hidden. Furthermore, we investigate with our reason (the proper function of which is to analyze) when, by analysis and investigation of the natures of individual things, we descend from universals to particulars. For every universal is more fully defined than its particulars: when we learn, therefore, we ought to begin with universals, which are better known and determined and inclusive; and then, by descending little by little from them and by distinguishing individuals through analysis, we ought to investigate the nature of the things those universals contain.

If this sounds at all vague or abstract, we will look at how Hugh makes it more practical and concrete in a moment. First, however, let’s notice that this is a preunderstanding that has to be brought to one’s method of interpretation. If a universal is impossible or concerns only the unreal, then a great deal of what Hugh is discussing would be eliminated. If a universal truth cannot help us to understand a particular thing, then our understanding of that particular thing will have to be based upon less that can be reasoned through, and more that will just have to be automatically and blindly accepted. Hugh is teaching that there are universals (be they goodness, evil, truth, falsehood, unity, disunity, etc.) which really shape and inform our approach to understanding particular things. If there are not, then we would be forced to confront and approach each individual thing without applicable concepts, standards, and tools to perceive and to interpret.

If this sounds at all vague or abstract, we will look at how Hugh makes it more practical and concrete in a moment. First, however, let’s notice that this is a preunderstanding that has to be brought to one’s method of interpretation. If a universal is impossible or concerns only the unreal, then a great deal of what Hugh is discussing would be eliminated. If a universal truth cannot help us to understand a particular thing, then our understanding of that particular thing will have to be based upon less that can be reasoned through, and more that will just have to be automatically and blindly accepted. Hugh is teaching that there are universals (be they goodness, evil, truth, falsehood, unity, disunity, etc.) which really shape and inform our approach to understanding particular things. If there are not, then we would be forced to confront and approach each individual thing without applicable concepts, standards, and tools to perceive and to interpret.

This matters when reading a text. But the analysis of a realist does not stop here. There is an underlying reason why there are four senses of Scripture, and there is a causal connection between being able to see how a text can signify multiple levels of meaning and applying different senses to the same text. Hugh summarizes this underlying reason, and he makes the “problem of universals” quite practical by applying it to language and reality in Book Five, Chapter Three of his Didascalicon, entitled “That Things, Too, Have a Meaning in Sacred Scripture”:

It ought also to be known that in the divine utterance not only words but even things have a meaning – a way of communicating not usually found to such an extent in other writings. The philosopher knows only the significance of words, but the significance of things is far more excellent than that of words, because the latter was established by usage, but Nature dictated the former. The latter is the voice of men, the former the voice of God speaking to men. The latter, once uttered, perishes; the former, once created, subsists. The unsubstantial word is the sign of man’s perceptions; the thing is a resemblance of the divine Idea. What, therefore, the sound of the mouth, which all in the same moment begins to subsist and fades away, is to the idea in the mind, that the whole extent of time is to eternity. The idea in the mind is the internal word, which is shown forth by the sound of the voice, that is, by the external word. And the divine Wisdom, which the Father has uttered out of his heart, invisible in Itself, is recognized through creatures and in them. From this is most surely gathered how profound is the understanding is to be sought in the Sacred Writings, in which we come through the word to a concept, through the concept to a thing, through the thing to its idea, and through its idea arrive at Truth. Because certain less well instructed persons do not take account of this, they suppose that there is nothing subtle in these matters on which to exercise their mental abilities, and they turn their attention to the writings of philosophers precisely because, not knowing the power of Truth, they do not understand that in Scripture there is anything beyond the bare surface of the letter.

Yes, this is a little mind blowing, but Hugh explains here a principle that lay behind the teaching of Cassian, and that would later be affirmed and explained in even more detail by Aquinas. Not only is this hard to argue with once it is fully reasoned out, but it is precisely what a Nominalist must deny. If particular things can signify meanings greater than themselves, then universals do exist in reality. From the realist point of view of Hugh’s metaphysics, the ideas of God were incarnated into things. Things are, therefore, physical incarnations of ideas from the mind of God. Thus when Scripture refers to things in the text, the words in the text have meaning, and the particular things referred to in the text also have their own meanings. Physical reality itself is composed of material embodiments of ideas and of universals. This is why the world has meaning. Nominalism denies this, and the result is not just a different view of the reality of physical things, but a different philosophy of language. To the nominalist, the meaning of words cannot directly correspond to the reality of things. Contrary to Hugh’s realism, the nominalist does not believe that, when dealing with a text, there is “anything beyond the bare surface of the letter.” Hugh’s realism, by contrast, avoids the extreme of the Gnostic,who denies the significance of physical things, and avoids the extreme of the nominalist, who denies the significance of words in the text.

But Hugh’s both/and teaching on meaning has yet another consequence. In the first part of this essay, we looked at how some Protestant theologians (such as Bernard Ramm, James White, and Wyman Lewis Richardson) argue that the only proper kind of hermeneutics is exegesis (taking meaning out of the text) and that eisegesis (bringing meaning to the text) is dishonest and deceitful. There are certainly some who would argue the opposite, that we can’t help but bring one’s own meaning/preunderstanding to the text, and that it is by pretending to conduct exegesis that one is really intellectually dishonest. Yet Hugh of Saint Victor does both. He certainly does eisegesis by bringing his metaphysics to the text, which fundamentally shapes how he interprets it. Eisegesis is, to Hugh, a conscious and intentional act, along with all the philosophical reflection that it ought to imply. But Hugh also conducts exegesis, affirming that a textual passage has a limited number of meanings that are really signified therein, and that the text must not be distorted in order to attempt to place more into it than is really there.