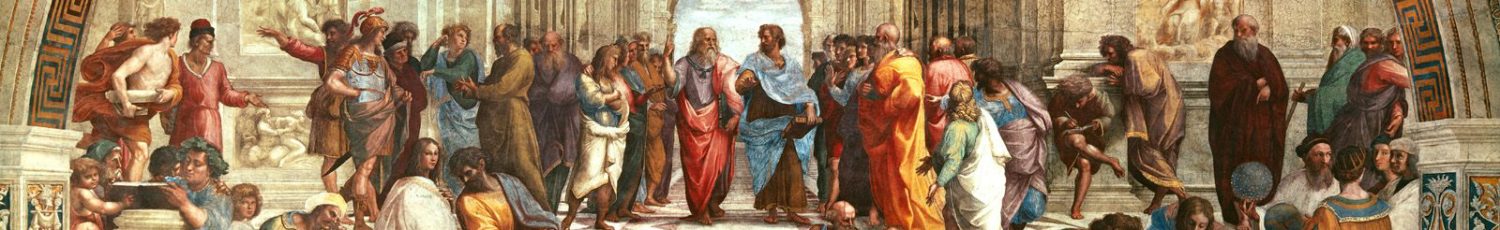

Is It Better to Suffer Injustice Than to Do Injustice?

I just finished teaching a class on Ancient Political Theory, which spent time reading Plato’s Republic. At the end of Book I, Thrasymachus bursts into the scene, defining justice as actions for the advantage of the stronger. Though he is eventually quieted due to his logical inconsistencies and constant overgeneralizations, Glaucon and Adeimantus recognize that Thrasymachus’ claims, if nuanced, would still present an important question. Thus, in Book II, Glaucon (taking on the role of devil’s advocate) seeks to determine whether justice is good in and of itself or merely as an instrumental means. Glaucon notes that it is the common opinion that people would do injustice if they could get away with it, but that people hate to suffer from injustice done by others. Thus justice arises by agreement in order to avoid suffering from the injustice of others (358e-360b).

When I recently read Kurt Schlicter’s article, “*Sigh*, No being a Christians does not require you to meekly submit to leftist tyranny”, I recognized a Thrasymachian bursting onto the scene, making sweeping generalizations and rhetorical flourishes that may sound sophisticated and appealing, but are mere sophistry which tickles the ears. Nuances are beyond Schlicter. Instead, he creates caricatures to argue against with exaggerated faults and imagined qualities while simultaneously failing to recognize a serious and legitimate question:

May Christians be called, on some occasions, to suffer the unjust actions of others, or are they called to always rise and fight at any cost?

A brief examination of the claims of Schlicter, compared with both Scripture and historic Christian teaching, may lead us to a challenging answer that is worth considering carefully. Schlicter notes “Resistance is not merely an option. It is a duty. And resistance to evil – because the desire to suppress our faith is evil – is not somehow unchristian because it can be aesthetically displeasing.” Christians have long recognized the importance of fighting evil, both of indwelling sin and in the world, but the Church has always argued that one must never do evil in fighting evil. For if the fight transforms us into the very thing we are fighting, then we have lost. This is why there the traditional historic discussion of moral principles Jus ad Bellum and Jus in Bello. Christianity recognizes that it is the way something is done, not merely the outcome that matters. This is important because it changes the question from “should it be done?” to “if done, how should it be done?” Thus, the question of “how should we then live?” requires a return to both Biblical and historical principles.

Schlicter, in what is one of his only passing indirect references to any Biblical passage in a column seeking to advise Christians, notes “Fighting back is not always pretty. Jesus cleared the temple of moneychangers. He made a mess and got people angry”. Schlicter is correct that the Gospels record this story (Mark 11:15-17; Matthew 21:12-17), but we must also wrestle with Jesus’ other statements, such as telling Peter to put away his sword (Matthew 26:52; John 18:11) and choosing to not call down legions of angels (Matthew 26:53). In examining these actions, we must seek to understand what makes them different? One occurs in the religious realm, where Jesus asserts his authority to fight error and evil, whereas another occurs in the political realm where Jesus is a citizen under authority. This difference may help us to elucidate how to understand and apply these actions.

It is also important to recognize that American Christians are not the first to think about, wrestle with, or deal with the questions of our relation and obedience to secular government. Martin Luther, in On Secular Authority, wrestled with the question of Mathew 5:39 “Do not resist evil.” He notes “From all this it follows that the right interpretation of Christ’s words in Matthew 5[39]: ‘You shall not resist evil etc.’ is that Christians should be capable of suffering every evil and injustice, not avenging themselves, and not going to court in self-defense either.”

This is because it is clearly worse to do wrong (sin and evil) than it is to suffer the effects of sin. This is because Christians are called to have a different time preference, in the hierarchy of focus for the Christian life. The eternal is always superior to the temporal. Thus our actions should be weighed by how they relate to our eternal soul, not just our temporal body. We must remember, as Jesus said, “[f]or what will it profit a man if he gains the whole world and forfeits his soul?” (Mathew 16:26). Our bodies, though they may suffer on this earth, will be resurrected and renewed in the new heavens and new earth, the scars and troubles will fade, but the impact of our character and ethical choices will always remain.

This change of focus is important because no longer is our focus on the present battle, but we are to focus on the strategy for the long war. Thus, Luther argues that Christians “should suffer their houses to be forcibly invaded and ransacked, whether it is their books or their goods that are taken. Evil is not to be resisted but suffered.” This sentiment is echoed by Calvin in his Institutes of the Christian Religion who said “but let us at the same time guard most carefully against spurning or violating the venerable and majestic authority of rulers, an authority which God has sanctioned by the surest edicts…let us not therefore suppose that that vengeance is committed to us, to whom no command has been given but to obey and suffer.” Here then we see where Schlicter breaks from the Christian tradition when he argues “You see, there is no combination of facts, rules, obligations, or commandments that requires us to take actions that will lead us to submitting to tyranny. I will not submit.”

Ultimately, we come back to the question of doing vs. suffering (active vs. passive).

Luther, continuing from the passage excerpted above, notes: “Of course, you should not approve what is done, or lift a finger or walk a single step to aid and abet them in any way.” It is absolutely important that Christians are called to serve others, not merely their own interests. Luther continues: “On the contrary [Christians] will require nothing at all for themselves from secular authority and laws [recht]. But they may seek retribution, justice [recht], protection and help for others.”

Our call to love our neighbors (Mark 12:31) means we are to seek justice for them. Thus, it is important to make the final distinction: between private citizens and public officials. Christians who serve in the government are called to seek justice, do righteousness, defend the poor and oppressed (Isaiah 1:17). Thus, Calvin continues his above statement by saying “For when popular magistrates have been appointed to curb the tyranny of kings … So far am I from forbidding these officially to check the undue license of kings that if they connive at kings when they [kings] tyrannise, because they [popular magistrates] fraudulently betray the liberty of the people, while knowing that, by the ordinance of God, they are its appointed guardians.” It is appropriate to petition and ask rulers to rule righteously and justly, and to pray for them to do so.

It is in understanding the key difference between realms (religious and secular) as well as roles (private vs public) that we can better understand the nuances of this debate. It is never wrong to suffer evil, but it is always wrong to do evil. Christians are not consequentialist. To determine if an action is praiseworthy or blameworthy it is important to examine the action and the internal motive, not just the outcome. Thus, Christian support for one specific political leader (which seems to be the primary purpose of Mr. Schlicter’s piece) needs to be assessed with less caricature and with more careful thought.

___________________________________________________________________________

Nicholas Higgins is married to Anita, father of 5 children, and holds a Ph.D. from the University of North Texas and a Master’s from University of Dallas. He is Assistant Professor of Politics at Regent University where he teaches political thought and institutions.